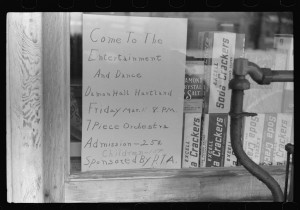

This picture is from the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. It was taken in 1940 and is credited to Marion Post Wolcott, 1910-1990, photographer.

Hartland History

posts which are of a specific topic

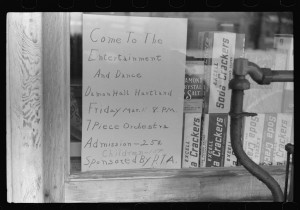

This picture is from the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. It was taken in 1940 and is credited to Marion Post Wolcott, 1910-1990, photographer.

This picture is from the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. It was taken in 1940 and is credited to Marion Post Wolcott, 1910-1990, photographer.

This is the Cowdrey’s house.

HARTLAND IN THE CIVIL WAR

(Second Installment, Jan. 2013)

by Les Motschman

This is the second installment of my attempt to follow Hartland men serving in the Civil War 150 years ago. As I explained in the first installment, this effort is based largely on Howland Atwood’s 1963 “Hartland in the Civil War.” He assembled a roster of Hartland men who served and described where their units were during the war. I also use several other sources, including information sent in by newsletter subscribers. I welcome personal information about your ancestors who served, as I want to make the connection to modern-day people who are living here or maybe grew up here. As you will read, I’ve so far made connections with some of today’s Hartland families, including the Bowers, Davis, French, Hatch, Howland, Lobdell, Tessier, and White families.

My first installment was concerned with the five regiments that made up the 1st Vermont Brigade, also known as the Old Vermont Brigade, including 17 volunteers from Hartland. [A brigade typically consisted of five one-thousand-man regiments.] This issue is concerned primarily with the formation of the 2nd Vermont Brigade, made up of Regiments 12 through 17. There were no Hartland men in the 13th, 14th, or 15th Regiments so I’ll write mostly about the 12th and 16th.

In the second half of 1862, over 70 men from Hartland entered the Army. Hartland men weren’t involved in much fighting in the fall of 1862, but the recruiting and filling the ranks of the 2nd Vermont Brigade so quickly is an interesting story in itself. This issue concludes with the massive battle at Fredericksburg, Virginia, in December 1862 between the Army of Northern Virginia led by General Robert E. Lee and the Army of the Potomac under new commander General Ambrose Burnside.

First, I want to recognize a few Hartland men who enlisted in Vermont regiments that were not part of the 1st or 2nd Brigades. Most, but not all, Hartland men served in Virginia. Henry H. Hastings enlisted in the 7th Regiment in February 1862 and served for five years. The 7th Vermont sailed from New York City to the Gulf of Mexico. New Orleans remained under Federal control throughout the war, but the Confederates controlled the fortifications on the bluffs at Vicksburg, Mississippi, which prevented the Union from using the river to move men and supplies to the Western Front of the war. The 7th participated in the Siege of Vicksburg in the summer of 1862, which was a series of failed attempts to take Vicksburg.

-1-

It was also at Baton Rouge when it was attacked by rebel forces trying to retake that part of the river. By the end of the year, the 7th removed to Pensacola, Florida. James Hutchinson also enlisted in the 7th in February 1862, but within a few weeks he died of disease. He is buried in the Plains Cemetery. Alonzo Martin joined the 7th in February 1862 from Woodstock and was discharged with a disability in June 1863. He represented the second of three generations to run a shop just across the Martinsville bridge.

On September 1, 1862, five Hartland men joined the 10th Vermont Regiment as three-year men. They were George Colby, Charles E. Colston, Charles D. Humphrey, Ira E. Hutchinson, and Seneca Young. On the same day, Edgar H. Leonard joined the 11th Vermont.

A few names were omitted in the first installment of September 2012. George C. Chase was with the 3rd Vermont Regiment during the Peninsula Campaign. Mr. Atwood did not mention Chase but includes him on the roster. Chase was discharged with a disability on July 29, 1862. David Wright was with the 6th Vermont Regiment during the Peninsula Campaign.

The First Regiment of Vermont Cavalry

In the first issue I mentioned that two members of the First Regiment of the Vermont Cavalry died in October 1862. This unit was organized in the fall of 1861 in Burlington. It set out for Washington on December 14, 1861, in 153 railroad cars. Mr. Atwood writes that such a grand cavalcade from Vermont was probably never seen before or since.

The first Hartland men in this unit were Oliver T. Cushman, Henry Holt, John Jelerson, Allen P. Messer, Benjamin F. Rogers, George Rumrill, and John H. Willard. Others joined in the ensuing years, including Clarence Cushman in September 1862. The twenty-year-old Oliver Cushman, a member of the Dartmouth class of 1863, enlisted as a sergeant (he would eventually be promoted to captain). His brother Clarence enlisted when he turned eighteen.

Early in the war, Union cavalry were mainly used for reconnaissance duty, checking the terrain and conditions ahead of the infantry. They were also employed as messengers as they had the only means of rapid transit. The Confederates used the cavalry as raiders from the start of the war. They would dash in through the Union picket lines, raid supplies, and be gone before anyone could stop them.

Bruce Catton, in his book Civil War, writes that “for the first half of the war Southern cavalry was far superior to the Federals. Jeb Stuart’s troopers could have taught circus riders tricks. Not until 1863 was the Union cavalry able to meet Stuart on anything like even terms. Most Southern recruits came from rural areas and were used to horses. The legends of chivalry were powerful, so it seemed much more knightly and gallant to go off to war on horseback than in the infantry. The Confederate trooper rode to war on his own horse often of blooded stock. There were plenty of farm boys in the Federal armies, but they did not come from horseback country; most horses on Northern farms were draft animals. Being well aware that it’s a lot of work to care for a horse, the Northern country boy generally enlisted in the infantry.”

The 1st Vermont Cavalry is credited with 75 engagements, mostly skirmishes, often with the opposing cavalry. Of the eight Hartland men in the 1st Vermont Cavalry in 1862, Messer was discharged with a disability May 22; Holt and Rogers died of disease on October 30, Rogers after release from a prisoner of war camp, and Rumrill was wounded August 29, presumably at the Battle of Second Bull Run and discharged with a disability on November 20. It must have been hard service, because without giving too much away, I will tell you that the other four men had very bad experiences before the war ended.

Two Hartland men from the 3rd Vermont Infantry Regiment transferred to the U.S. 5th Cavalry on October 30, 1862. George H. Barrows had just enlisted; Fred Blaisdell had joined in July 1861 and experienced the Peninsula Campaign and the Maryland Campaign.

-2-

Lincoln calls for 300,000 volunteers

After General George McClellan’s disastrous Peninsula Campaign with its high losses, and recognizing the need for more men in the Western Theater of the War, President Abraham Lincoln in 1862 asked the Union states for another 300,000 volunteers. Enthusiasm for the war had radically changed from a year earlier when men had flocked to enlist. Initially it was thought that the North with its larger population and far superior industrial base would be able to put down the rebellion of the mostly agrarian South rather quickly. Indeed, as is the case in any war, many young men rush to volunteer not wanting to miss out on what might be the adventure of their lives. After the first few months of fighting, it was clear that victory would come only at a great cost of men and matériel and might take years.

By mid-1862 the casualty lists published in local newspapers were growing, and crippled veterans had returned home with tales of the horrors of war. Coffins were arriving as well, mostly of soldiers who succumbed to disease. Those who died in a large battle were more apt to be buried where they fell or in a cemetery created on the battlefield. Of the four Hartland men who had died by this time 150 years ago, three-Holt, Hutchinson, and Vaughan-are buried in Hartland cemeteries. Benjamin Rogers is buried in Washington, D.C.

Just as enthusiasm for the war was waning, the need for more men was growing. Vermont had finished raising the 10th and 11th regiments with three-year enlistees, and the militias were depleted. Lincoln asked the states to raise the troops because the Federal government did not have authority to draft men into service. On July 17, 1862, Congress passed a “Militia Law” declaring that all able-bodied men between the ages of 18 and 45 were legally part of the militia. The law empowered the President to call the militia into Federal service for nine months. The War Department realized that most men with families and a farm or business were not eager to enlist for three years; thus, the creation of “Nine Months Men.”

Some of my information about the recruitment and deployment of Vermont’s 2nd Brigade comes from Howard Coffin’s book Nine Months to Gettysburg. Coffin calls his native Woodstock the “Pentagon of Vermont” in that Vermont’s war effort was run by Vermont’s Adjutant General, Peter Washburn, from a building on The Green. Washburn was a Woodstock native and a lawyer, and had led 500 Vermont troops of the 1st Regiment during the Peninsula Campaign. Vermont’s quota was 4,898 men, and the Adjutant General’s office worked day and night to get the quotas out to all town officers, as it was their responsibility to furnish the men requested.

The Vermont Humanities Council’s weekly Civil War newsletter of September 7, 2012, notes countless town recruiting meetings held across the North. It describes a meeting in Windsor as being large and enthusiastic, packing the Town Hall while a large crowd gathered outside, vainly trying to learn of the success within. The Windsor Coronet Band enlivened the meeting with patriotic music. Patriotic speeches were made, and a number of citizens encouraged enlistments by generous donations. The men came forward, the quota was filled, and the meeting adjourned amid enthusiastic cheers.

As almost all the men enlisting were volunteers, I had assumed they were marching off to war to do their patriotic duty to try to save the Union. The U.S. Army paid them $12 to $14 a month. It wasn’t until I started this project that I saw the term “bounties.” It seems that towns appropriated money at Town Meetings to pay the men who enlisted. I attended a talk Howard Coffin gave last Fall about “Nine Months Men.” He told me bounties ranged from $50 to $1,000. Towns competed for recruits; most men would sign up in the town they lived in, but some would enlist in neighboring towns, especially if that town was paying higher bounties. Coffin said $300 was a typical bounty, but as the war wore on and still more troops were needed, men could receive two or three times that if towns were having trouble meeting their quotas. To put these dollars into perspective, a laborer at that time made a dollar a day, and Coffin said one could buy a farm for a thousand dollars.

I asked Hartland Town Clerk Clyde Jenne if we have minutes for Town Meetings in the 1860s. He said no, but I should look at the Town Reports. The February 1863 Hartland Town Report is only eight pages; all the soldiers are listed by name, grouped by how much bounty they were paid. The Nine Months Men received $100. For some

-3-

reason, men who enlisted for three years got only $50. Total orders drawn by the Selectmen that year amounted to about $6,200, and nearly $5,000 of that was to pay bounties. $3,100 was borrowed to pay the bounties. Clyde said the town went deeply into debt during the Civil War and did not finish paying off the debt until decades later.

Following is a list of men who enlisted in the fall of 1862. Members of the 12th and 16th were mostly Nine Months Men. The men who enlisted in the 1st Brigade regiments were generally three-year men. Men whose names are marked by asterisks (*) enlisted in nearby towns but were born and/or buried in Hartland.

The men who enlisted in the 2nd Vermont Brigade were transported by trains to Brattleboro where they were marched to a high plateau a mile from the station that was becoming Camp Lincoln. The 4th and 8th Vermont Regiments had already camped at Brattleboro on their way to war. With the large influx of new recruits coming, the early arrivals, including the 12th, were put to work building more barracks. In Nine Months to Gettysburg, Howard Coffin says the men were drilled hard but adjusted to camp life and were able to relax some in the evening and on weekends.

Coffin makes great use of personal first-hand accounts from the soldiers’ letters home. He notes that our Private Benjamin Hatch of the 12th was troubled by soldier morality. The thirty-five-year-old Hatch was one of the older recruits. He wrote to his wife in Hartland: “Is as much as 20 playing cards and gambling every night….Last night I went along the line of camps, some were gambling, some were swearing, some were dancing and everything else you can think of.”

-4-

On October 7, 1862, the 12th Regiment was the first to leave Vermont for Washington. Since Coffin says most of the men had never been even to Massachusetts, it must have been interesting for them to see hundreds of miles of countryside and stop in the country’s major cities of New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, and then end up in sight of the Capitol. Like the soldiers in the 1st Brigade a year earlier, the 12th marched through Washington and camped at the fortifications near the Potomac. Within a few days they crossed the Potomac and marched to Camp Vermont where they would spend the winter.

Camp life consisted of drill, readying the shelters for winter and picket duty. Each day a portion of the men were marched out of camp to take up positions on the miles-long outer defense line of Washington. Coffin reports that when the soldiers had a day with no duty, many went to see the sights of Washington or visited Mount Vernon. Private Hatch wrote, “If we can go a little ways from our camp, we can look down into Alexandria and onto Washington and see the shipping on the Potomac. For miles it is quite a scenery.”

Reports are that some of the men suffered from the October heat in Virginia, but winter arrived early that year. Soon cold, rain, and snow were making life miserable in the camp. The many letters exchanged between the soldiers and their families back home confirm that more snow fell that winter on Camp Vermont than on the real Vermont. As usual for the camps, sickness among the soldiers was widespread.

Eighteen-year-old Charles Rodgers died of disease on November 3, 1862, just one month after mustering into the Army at Brattleboro. He was one of four young Rodgers from Cream Pot Road to enlist in the 12th Regiment that fall. I don’t claim descent from any of the Hartland Civil War veterans, but Charles seems like a neighbor. I visited his grave soon after moving to Weed Road over 35 years ago. For a long time, I didn’t know how long he had served or how he died. He is buried in Weed Cemetery next to his parents.

Reuben Lamphear died of disease on December 7, 1862. He is buried in the Plains Cemetery.

Howland Atwood’s notebook includes a collection of newspaper clippings from 1963 Rutland Heralds. It was running “100 years ago” columns. One states that, “The mortality rate in our armies in 1862 was 67.6 deaths per 1,000 men. Disease accounted for 50.4, wounds and injuries 17.2.”

Thanksgiving was celebrated heartily in the camps. President Lincoln declared it a national holiday in 1863, but celebrating on the last Thursday in November was already a well-established tradition. The Vermont Humanities Council newsletter describes that week in Camp Vermont through letters home from a member of the 12th Regiment who had been a machinist at the gun factory in Windsor. They were working on their “houses” built of stone, wood and canvas:

We have been very busy all day on our house. Two or three more days of good weather and we can move in. Thanksgiving has really begun here in this company. There arrived here tonight from West Windsor and other places one barrel and many boxes the size of boot boxes, you may guess there was something for everybody. The boys in this tent got a large quantity, so I guess I shall have something for Thanksgiving, as they are very generous. I will name a few things that came to friends. There was a half of cheese, four or five pounds of butter, about 2 gal. of applesauce, a baked chicken, a lot of cakes, about three pints of butternut meats, six pounds of maple sugar, a few chestnuts and a number of little things too numerous to mention. As far as I have heard, it all came through without hurting the least thing.

[I remember being amazed many years ago reading about a mother in Vermont roasting a turkey and the father boxing it up with some other things and taking it to the depot. The son in camp in Virginia received it two or three days later in good shape. The railroad didn’t come to Hartland until 1849. The building boom continued through the 1850s, and by the time the war started in 1861 the railroad system was pretty well established, so people, goods, and mail could travel much faster than just a of couple decades earlier.]

Christmas seems to have been observed in a more somber manner. The men had the day off except for essential duty, but they weren’t feasting or celebrating.

-5-

First Fredericksburg, Virginia, December 13, 1862

According to the Vermont Humanities Council newsletter, President Lincoln waited until the day after the 1862 mid-term elections to relieve General McClellan as Commander of the Army of the Potomac, timing the removal so as to not alienate Democrats. General McClellan said, “They have made a great mistake,” and ran against Lincoln two years later. General Ambrose Burnside reluctantly accepted command of the Army from Lincoln. General Burnside promptly submitted a plan for a direct move on Fredericksburg, and then south to Richmond. It was important to occupy the heights above the town before General Lee’s army arrived. The bridge across the Rappahannock River had been destroyed, so pontoon equipment was immediately ordered to be brought from Harper’s Ferry where it was being used. The river could have been forded, but Burnside was afraid the water might rise and separate his 120,000 soldiers. By the time the bridge was ready, General Lee was waiting on the heights with 113,000 men. Fredericksburg was now nothing but a trap.

The Union army was divided into three divisions led by Generals Edwin “Bull” Sumner, Joseph Hooker, and William Franklin. The Vermonters in the 1st Vermont Brigade (Regiments 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6) were under the command of General Franklin, whose division was on the left of the battle line. Cold weather arrived long before the pontoons did, bringing rain, snow, and general discomfort. Burnside waited and Lee watched. The Confederates were on the western hills known as Marye’s Heights, where their guns commanded the flat land below as well as the town.

On December 11, 1862, the Union army started to cross the river. Franklin’s troops found little opposition, but General Sumner’s division on the right had a difficult crossing. Rebel sharpshooters mowed down the bridge builders.

In heavy fog on the morning of December 13th, Burnside’s assault commenced. The three divisions groped through the fog across the road and railroad tracks along the river. When the fog lifted, the Confederates saw waving flags and the gleam of tens of thousands of bayonets. J.E.B. Stuart’s artillery poured heavy fire into the Union left flank. The Union batteries across the river joined the battle, silencing the Confederate fire. Under cover of their own guns, Franklin’s army heaved forward into woods at their front, only to meet short-range small arms fire from Southern infantry embedded in the thicket. The whole Union force was pushed back onto the plain. All afternoon the fighting raged back and forth, and the day ended with the Union and Confederate positions the same as at the beginning.

General Sumner’s division on the right had it even worse. As those men moved up the open land below Marye’s Heights, the Confederate guns there opened fire. At 200 yards the Confederate infantry opened fire from the sunken road and stone wall, and three Federal brigades in succession melted away. The Confederates were four deep behind that wall. Still more men were sent up the hill. Hooker’s division was ordered into action. Burnside was adamant: “That height must be carried this evening.”

It never was. Fourteen gallant attacks were made that day. Thank God Franklin was beyond Burnside’s reach. Between the hostile lines, 12,500 fallen Union soldiers lay dead or wounded in a succession of ghastly windrows, 6,000 of them in front of Marye’s Hill. Lee’s losses were about 5,300 in all. One brigade left behind 545 men in the frozen mud. The wounded lay for up to 48 hours in the freezing cold. Some burned to death where cannons set fire to long grass.

[The description of the battle is from Atwood’s notebook. He relies mainly on The Compact History of the Civil War to provide a narrative of the War where Vermonters were present.]

It was at Fredericksburg that General Lee, watching his troops wreak havoc on the Union Army, uttered this famous line: “It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it.”

Fredericksburg may have been the worst Union defeat of the war, but apparently no Hartland men were seriously hurt. Of course by my estimate they represented only two dozen of the 120,000-strong army. William Petrie of the 4th Regiment was discharged with a disability January 31, 1863, so it’s possible he was wounded there. At least one

-6-

Hartland native was killed during the battle. Twenty-eight year-old Charles Ballou was living in Claremont when he joined the 5th NH Infantry in October 1861. Ballou was a 1st Lieutenant by the time of Fredericksburg, so he may very well have died leading his men up the slope in front of the sunken road. Hartland resident, Greg Chase, a re-enactor for the 5th NH, says the regiment was in one of the early attacks toward the road and came as close to reaching it as any unit, but took heavy casualties and was beaten back.

The new troops of the 2nd Vermont Brigade were not at Fredericksburg, but they could hear the battle forty miles away. Soon they were starting to get reports of the terrible slaughter and defeat. This was met with a sense of dismay and disgust at the handling of the battle. As word spread, this was the reaction throughout the army and the North. General Burnside became known as “The Butcher of Fredericksburg.”

Incredibly, Burnside wanted to attack the next day, but his shocked and almost mutinous corps commanders talked him out of it. He was halted by President Lincoln’s firm order to take no action without informing him. Burnside blamed his generals for the failure. Franklin was replaced by General John Sedgwick after the battle. On January 25, 1863, Major General Joseph Hooker relieved Burnside as Commander of the Army of the Potomac.

The term “sideburns” comes from his last name.

Addendum

On a political note, after our long electioneering year of 2012, when some have said the country is more divided than at any time since the Civil War, and the President and Congress seem unable to accomplish anything, it was interesting to read political writer George Will’s last column of the year.

He wrote:

In 1862, the grim year of Shiloh [Antietam] and Fredericksburg, Congress would have been forgiven for concentrating only on preventing national dismemberment. Instead, while defiantly continuing construction of the Capitol dome, Congress continued nation building. It passed the Pacific Railroad Act [which led to the completion of the Trans-continental Railroad in 1869]. It passed the Morrill Act [named for Vermont Senator Justin Morrill] to build land-grant colleges emphasizing agriculture.

Most important, Congress passed the Homestead Act, which Will describes as the “first comprehensive immigration law.” The act was intended to attract immigrants from abroad who would put down roots. For this purpose it provided all the requirements for citizenship. For $18 in fees, a homesteader was entitled to 160 acres in the Great

Plains [then known as the Great American Desert]. After they farmed the land for five years, it would become theirs, and they could become citizens. The land was sparsely inhabited, mainly by Native Americans; and with so many citizens fighting, an Illinois congressman proclaimed that “noncitizens were needed to go upon these wild lands to increase the nation’s wealth.”

-7-

Family Connections

I surmise that the hundred men on the rosters must have hundreds of descendants born in Hartland. I will note some of the connections to families living in town now or within the last couple of decades. Mr. Atwood mentions several descendants of veterans, but his list ends a couple of generations ago. Some of you have provided me with your family connections to Civil War veterans and I hope you continue to do so.

Thanks to my wife Susan for her contributions in the typing, layout and finished product of this project.

We are fortunate that Pat Richardson is editing my work. Her expertise in this field greatly improves the readability of the final version.

Les Motschman

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

A Note From Carol

A big thank you to Les for doing the research and to Les and Susan for putting together this newsletter. The work that they are doing is of huge value in understanding Hartland’s role in the Civil War.

-9-

Reprinted from the January 2013 Hartland Historical Society Newsletter. Page breaks and numbers were preserved to assist in references to specific pages of this document.

Correspondent, Miss Florence H. Sturtevant.

Miss Bertha Mower injured her thumb recently, when a butcher knife fell and cut it.

Miss Wilma Emery is in Everett, Mass. She returned with her uncle, Dr. Fred Richmond and family, who were here over the week-end.

Rehearsals are being held Monday nights by the choir, in preparation for a concert to be given sometime in July. The weekly Thursday night choir practice is also being held.

Mrs. Mildred Andrew has been appointed local correspondent for the Woodstock Standard, in place of Mrs. Louise R. Sturtevant who died last week, and who had held the position for more than 35 years.

The primary school, with the teacher, Miss Merriam, had a picnic at the Rockwood farm yesterday afternoon.

Miss Clarice Gilpin returned from Middlebury college Wednesday.

Howard Emery has been quite sick with summer grip.

Date: June 9 1933; Newspaper published in: Rutland,Vt.

Source: Rutland library microfilm

Culverts are openings beneath roads and railroad lines generally constructed out of stone. They were used where a full fledged bridge was unnecessary. Culverts originally were built to form a dry, hard surface over small streams. Later on with railroads crisscrossing farm lands animal underpasses were added. Most culverts are below the road surface. Hence, soil was built up over culverts reinforcing their stability and longevity. Culverts did not require maintenance on annual basis as does a bridge. Culverts range from stones slabs laid across a stream to walled and roofed openings.

Culvert Ellison Rd. beyond Poor Farm Rd. near Rockwood Farm. Photo by Steve Howard.

Large flat stone slabs were laid atop low stones. This allows water flowage underneath and creates a solid firm surface across the stream. Water softened earth on edges of either side of culvert were paved with flat stones.

HARTLAND IN THE CIVIL WAR

By Les Motschman

Introduction

Most of you know that America is marking the sesquicentennial of the Civil War, fought 150 years ago, 1861–1865. Many Americans have been interested in learning about the Civil War ever since it was fought. It touched just about every person in this country at that time; if you had ancestors living here in the mid 1800s, you probably have some family connection to the War.

Perhaps we are still interested in learning about the Civil War because it was such a large-scale conflict fought entirely on American soil and pitted Americans against Americans. The scale of destruction and the number of casualties is something we cannot relate to today, but it is still possible to visit many well-preserved battlefields, mainly in the South and especially Virginia. Indeed, there is such a treasure of information about each action and who served where that it’s possible you can know where your ancestor was 150 years ago and go there yourself.

The Civil War has interested me since its centennial was commemorated in the early 1960s, much like the 150th is being recognized today. When I was in my early teens, events that happened 100 years before seemed like ancient history. Now, fifty years later, 100 years doesn’t seem like such a long time.

My plan is to contribute an article to each HHS newsletter for the duration of the sesquicentennial. I will write about where Hartland men were serving and also what was happening on the home front. This is possible because the HHS has a thick notebook entitled “Hartland in the Civil War,” compiled by the Hartland historian Howland Atwood (1918–2010). He completed the book in October 1963, presumably motivated by the Civil War’s Centennial. The notebook includes detailed lists of Hartland men and when they served with a particular regiment. Also included is some general Civil War history of battles they participated in, but not much in the way of personal stories.

To make this project more interesting, I hope HHS members will submit information about their ancestors’ experiences (letters home, diaries, family history). I recognize many 20th century Hartland names on the rosters, such as Allen, Bowers, Durphey, Martin, Rogers, Rumrill, and Spear. I would appreciate any help in establishing any connection between the men on the rosters and latter-day Hartland residents. Mr. Atwood footnotes his sources and provides fifteen sources in a bibliography. His main source seems to be The Complete History of the Civil War, published in 1960 by Hawthorne Books, Inc. I will not cite Mr. Atwood’s references, but those interested can find the notebook in the HHS collection. When I personally provide information, such as to connect soldiers with modern-day places or people, I will add that info italicized in brackets. To track events, I will also use “The Civil War Book of Days,” a weekly newsletter published by the Vermont Humanities Council that commemorates what happened each week 150 years ago (vermonthumanities.org).

Since the Civil War started in April 1861, it had been going on for a year and a half by this time 150 years ago. I will use this issue of the newsletter to catch us up to September 1862.

In 1861, the United States Army consisted of fewer than 20,000 officers and men in widely scattered companies. The “militia,” 3 million strong on paper, was in fact a huge, unorganized mob. The President could call it to duty, providing the various state governors complied. A 1795 law limited service to three months.

Vermont, of course, promptly rallied to the cause. In a proclamation, Governor Erastus Fairbanks called the State Legislature to convene on April 23, 1861. On the first day of the session, the legislature appropriated an unprecedented sum of $1 million for war purposes. The First Regiment of Vermont Volunteers consisted of militia companies from several towns, including Woodstock. Hartland’s first Civil War soldier was 29-year-old Horace Bradley, who joined the Woodstock company. He was brought up on Densmore Hill near the Woodstock town line [probably the Norman Williams place]. The First Vermont trained in Rutland for a few days, and then left for Fortress Monroe near Hampton, Virginia.

The first objective of the Army was to secure the nation’s capital, just across the Potomac from the rebel state of Virginia. Several Hartland men joined the Third Vermont Regiment in the early summer of 1861. The Third Regiment arrived in Washington on July 26, 1861, marched six miles up the Potomac and laid out Camp Lyon to protect a bridge, a reservoir, and other waterworks. Charles Allen, Roderick Bagley, Fred Blaisdell, Andrew Kezen, Thomas F. Leonard, and Zing Walker were with the Third at that time. The regiment was reviewed at Camp Lyon by President Abraham Lincoln. Several Cabinet members and top Union Generals Winfield Scott and George B. McClellan were also present.

Back in Vermont, the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Regiments were assembling. In late September 1861, these new recruits arrived in Virginia to join the Third Regiment at its new camp across the Potomac from Camp Lyon. Hartland men in the Fourth were Gideon Bennett, Charles H. Cleveland, James French, William Petrie, and Orlando Vaughan. Thomas Kneen of Woodstock came with the Sixth [after the war he owned the farm on Hartland Hill now owned by Andy Stewart].

In October 1861, the men marched four miles into enemy territory and established their winter quarters near Langley, VA. There was very little fighting during the winter months when the men mostly trained, but typhoid, diphtheria, measles, mumps, and all manner of sickness plagued the men all winter and took a heavy toll. Orlando Vaughan died of disease December 2, 1861.

THE PENINSULA CAMPAIGN

Once enough troops had arrived in Washington to defend the capital, the Union Army could mount a massive offensive assault on the Confederate capital at Richmond. Richmond is only ninety miles south of Washington, but the plan was to attack from the sea, moving up the peninsula formed by the York and James rivers.

On March 10, 1862, the five regiments, which were known as the “Old Vermont Brigade,” abandoned camp and marched to Alexandria. Two weeks later, they sailed down the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay to Fortress Monroe at the end of the peninsula.

If you’re wondering, there was a Second Regiment. Formed soon after the First, it was the first three-year regiment raised in Vermont and it formed a brigade with regiments from Maine. There were no Hartland men in the Second, although there were four “substitutes” for Hartland men—apparently out-of-town men were hired by Hartland men to go in their place. Three deserted, and the fourth was taken prisoner.

While the Federals were massing at the end of the peninsula, the Confederates were moving down from Richmond and building strong fortifications to hold back the expected Federal onslaught. When the army advanced up the peninsula on April 4th, General McClellan seemed surprised to be confronted by such formidable entrenchments and ordered a complete halt. Actually, many of the cannon turned out to be black-painted logs. When it was finally decided to try to break and turn the Confederate line, Vermont’s Third Regiment was chosen to lead the daring assault.

The attack was a success. The enemy line was broken, and the Union Army could have advanced; but no reinforcements were sent to follow the Vermonters’ brave attack. After holding their position for an hour, the Vermonters were called back. Of the nearly 200 men who attacked, nearly half were killed or wounded, although apparently no one from Hartland was seriously hurt. What might have been the start of a brilliant campaign for the North and an early cessation of hostilities became known as the Siege of Yorktown. The drive up the peninsula was stalled for a month as soon as it started.

The Green Mountain Men engaged the Confederates in fierce fighting on two more occasions while near Yorktown. Both times, General McClellan ordered the men back into the Union lines. These frustrating results were typical of his management of the Army. The magnificent Army of the Potomac, as it was known, was McClellan’s creation. He was popular with his men and an able strategist, but his hesitancies and tendencies to overestimate the opposing forces were eventually his undoing. The advance of the 100,000-strong Union Army was held back by 15,000 Confederates. Meanwhile, the Confederacy steadily increased its forces, no doubt prolonging the war.

While General McClellan overestimated the strength of the Confederates, General Joseph E. Johnston, the Commander of Confederate forces, knew he was vastly outnumbered. General Johnston received permission from Confederate President Jefferson Davis to withdraw to Richmond. When General McClellan learned that the Confederates had left, he ordered an immediate pursuit. The Army of the Potomac caught up to the rear guard of the Confederates near Williamsburg on May 5, 1862, and General Johnston ordered a counterattack. The Third Regiment was active in repelling the Confederate attack. It experienced hard service at Williamsburg and in the Seven Days Battles that followed.

The Seven Days Battles lasted from June 26 to July 2, 1862, consisting of a series of actions as the Union Army of the Potomac pursued the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, so named by General Robert E. Lee, who took command after General Johnston was seriously wounded. All five Vermont regiments, of course, participated in the pursuit; but with both armies moving up the peninsula, on some days one regiment might be in the thick of the battle while others were holding the Union line but not directly engaged. The exception was the Sixth Regiment, which was constantly in front. White Oak Swamp was the worst fighting as men fought in water up to their waist. After nearly two days of battle, a truce was called so both sides could retrieve the dead and wounded.

The Battle of Malvern Hill ended the Seven Days Battles and the Peninsula Campaign. It was a clear-cut Union success and might have been hailed as a great victory, save for one thing. General McClellan ordered his victorious army to retreat down the peninsula, leaving the field to the astonished Confederates. Some of the Vermont units had come within ten miles of Richmond.

THE MARYLAND CAMPAIGN OF 1862

After the Peninsula Campaign, the Vermont Brigade remained in Virginia for nearly two months without engaging the enemy. By the last week of August, it was on the move again. General Lee had secured Richmond and was moving his army north. The large battle of Second Bull Run was fought at Manassas August 26th and 27th. The Vermont Brigade was marching nearby and heard the fighting but was not engaged. Encouraged by a decisive Southern victory at Manassas, General Lee moved to invade the north.

On September 14, the five Vermont regiments, along with 18,000 other Union troops under the command of General William B. Franklin, encountered Confederates near Harper’s Ferry and the march was stalled.

[Note: Although I haven’t mentioned the formation of any Vermont regiments beyond the Sixth, men were enlisting throughout 1862; I will describe their service in later installments. Mr. Atwood does note that James Fallan and Daniel Patch of the Ninth Vermont were at Harper’s Ferry. They entered the army in July. Patch deserted but eventually returned to his unit and was discharged with a disability November 21, 1862.]

BATTLE OF ANTIETAM, MARYLAND, SEPTEMBER 17, 1862

Antietam was the bloodiest day of the Civil War. The two massive armies came together in a dawn-to-dusk battle in which 24,000 men fell; 4,800 died that day, and many more died later of their wounds. Thousands of bodies lay in lines as they had fought; bodies lay in the Sunken Road five feet deep. The Vermont Brigade came late to Antietam and was put with the reserve troops. Although it was under fire, the Vermont Brigade must have missed the worst fighting, for no casualties have been noted for Hartland men at that battle.

After the battle, General Lee withdrew his battered army south across the Potomac and awaited General McClellan’s attack. It never came. True to form, General McClellan did not pursue, even though he had two fresh corps, including the Vermonters. Thus, yet another opportunity to crush the rebel army and end the war was missed.

The Vermont Brigade spent October 1862 resting at camp in Hagerstown, Maryland. On November 7th, General McClellan was replaced by General Ambrose Burnside.

SUMMARY

To recap, 11 of the 14 Hartland men in the Vermont Brigade fought their way up the peninsula, skirted the major battle of Second Bull Run, engaged the rebels in Maryland and were at bloody Antietam, yet remained unscathed. Horace Bradley’s three-month enlistment was up after the Peninsula Campaign, so he returned home. Orlando Vaughan died of disease before any action. Charles Cleveland was discharged with a disability on December 27, 1861.

There were other Hartland men fighting in the war in regiments I haven’t introduced yet and who died in 1862. Two men from the First Vermont Cavalry died of disease on October 30, 1862. Henry Holt and Benjamin Rogers joined the Cavalry in November 1861. Rogers was taken prisoner May 24, 1862, while in the Shenandoah Valley. He was released September 13, 1862 and died a month and a half later. Many more Hartland men entered the army in 1862. Their service is the subject of the next installment.

Reprinted from the Fall 2012 Hartland Historical Society Newsletter.

By Jon Wolper, Valley News Staff Writer

Published in print: Thursday, April 25, 2013, used with permission.

Jason Norris, who works for contractor Jan Lewandoski, measures the outside of the steeple of the Hartland Unitarian Church in Hartland Four Corners yesterday. (Valley News – Sarah Priestap)

Hartland – Since the mid-1850s, a white steeple has sat atop the First Universalist Society of Hartland’s white, wood-paneled house of worship building.

Yesterday, for the first time, it was taken down.

The move, accomplished by crane, is the first of several aesthetic and foundational restorations that church leaders plan to do to the steeple and building itself.

The renovations, which will include work on the church’s exterior and parking lot, began with a capital campaign launched in September, said Paul Sawyer, the church’s minister. At the time, he and others had one chief concern:

“Can we raise $100,000 in this little congregation?” he said.

Since the campaign kicked off, the congregation has raised $93,000. Recently, it was awarded a $20,000 grant from the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation, as well as a $5,000 grant from the Jack and Dorothy Byrne Foundation.

Jason Norris climbs down from inside the steeple after it was removed. (Valley News – Sarah Priestap)

The rest, though, has come from the church’s 103 members, as well as other supporters, Sawyer said.

“The community has been wonderful,” said Sue Taylor, who applied for the grants. “They’ve really supported this.”

The project, which will include restoration by Jan Lewandoski, who specializes in historical restorations, will cost about $50,000, Sawyer said.

The rest of the money will go to parking lot and exterior renovations, as well as other structural and foundational work, such as improving drainage.

“It’s really working on the bones of the building,” he said. “It’s been here for 160 years.”

At about 9:15 a.m., about 45 minutes after the 88-foot, 3,000-pound structure had been removed, a small group of church members gathered on the building’s lawn at Hartland Four Corners. In front of them, in a rare close-up, stood the steeple, its white paint heavily peeled and its highest point broken.

The jagged wood at the top of the steeple used to hold its cast iron weather vane, which was knocked off its perch during a storm a year ago. Church President John Osborne said it “shattered into a gazillion pieces.”

Yesterday, while the steeple was being taken down, a handful of small shards of wood, each with splotches of cracked, time-worn paint, broke off the structure. Osborne found one in the parking lot, and showed it to Taylor. He called it his “historical souvenir.”

Lewandoski said that the boarding on yesterday’s specimen had begun to rot. That wasn’t an issue, though, as the boarding acts as a cover – the framing, the guts of the steeple, hadn’t been harmed.

“They caught it at the right time,” Lewandoski said.

A miniature replica of the Hartland Unitarian Church is seen adjacent to the larger, more habitable version after the steeple was removed in Hartland Four Corners yesterday. (Valley News – Sarah Priestap)

Previous work on the steeple had been done both 20 and 12 years ago, Sawyer said. In the 1990s workers shored up the roof underneath the bell, he said, and a dozen years ago they fixed some rotting planks.

But that work was done with the steeple still intact. A 1994 photo of the restoration shows a man scaling the structure with a rope.

This time, of course, is different.

“All the sheeting’s going to come off,” said Sawyer, standing near the towering steeple with Lewandoski. “He’s going to make it last another 150 years.”

To celebrate the project, which does not yet have a set finish date, church members will hold a “Save the Steeple Celebration” on May 31. It will begin at 6 p.m. with a dinner and ringing of the church’s bell, which was built in 1834, according to Lewandoski, and then feature a talk from the restoration specialist at 7:30.

By Ben Conarck, Valley News Staff Writer, Monday, April 15, 2013,

(Published in print: Monday, April 15, 2013). Used with permission.

Hartland — A team of archaeologists hired by the president of VTel to exhume a cemetery located on his 173-acre estate have unearthed fragments of Upper Valley history nearly two centuries old, but not without dredging up some new questions too.

The relocation of the cemetery, which occupied land purchased by VTel CEO and President Michel Guite, stirred up resistance from residents and led to a three-year legal battle over the rights of descendents to access the burial plot.

The case went all the way to the state Supreme Court, which sided with Guite in late 2011. Jerome King, a Hanover resident who has since died and whose family owned the property for 33 years, sued to prevent the unearthing of the cemetery where the ashes of his cremated parents were laid to rest.

[Although the cemetery move was controversial], most of those in attendance expressed only fascination as Kate Kenny, an archaeologist with the University of Vermont team who helped lead the dig at what’s known as the Aldrich Family Cemetery, gave a detailed presentation of findings yesterday at the town’s library.

After going through the history of the Aldrich family, who settled their farm on the property in the early 1800s, and the subsequent history of the cemetery land itself after it left family hands, Kenny began to work through an inventory of items unearthed at the site, slide-by-slide, in a post-mortem of sorts that shed plenty of light on the lifestyle of 19th century Vermont farmers.

“This is kind of where it’s fun, where we start analyzing all the information, everything we’ve found,” said Kenny. “There’s maybe a little bit of CSI going on, but you use everything you can to try and reconstruct, and in this case, none of the coffins survived.”

Due to the type of the soil where the burial plot was located, Kenny explained, there were very few personal items recovered from the grave sites. But she added that was also due to the burials occurring in the earlier half of the 19th century, a time when people were rarely buried with their jewelry, or even in their own clothes.

Some of the later graves at the site had hardware from the coffins such as nails, screws and hatches, which clued archaeologists in on the types of coffins used there, during a time before bodies were embalmed prior to their burial.

“The cemetery is at the one tradition of burial and bordering another,” Kenny said.

As for the lengthy archaeological process, that too was complicated by outside factors. At one point in the presentation, the room erupted into laughter when Kenny explained what had led to delays by clicking to the next slide: an image of a burrowing creature standing on its hind legs with an expression that almost told of the critter’s satisfaction with its natural role.

Burrowing creatures apparently went to work all over the cemetery grounds, displacing earth and human remains in the process. Kenny said that once the crew found a part of a corpse that had been carried closer to the surface by a creature above a marked grave site, it had to stop digging with machines and start excavating by hand.

Going into the dig, Kenny said, she expected to find a maximum of 10 bodies buried there, which she did find, not to mention a family cat. But that’s where the unanswered questions come in.

“The thing is, I found 10 people, and the cat, but some of them were different people (then who she was expecting),” Kenny said.

While she has some “leads” on the two unidentified bodies uncovered there, Kenny couldn’t pinpoint exactly who the people were, despite employing all the research tools at her disposal.

After the presentation, John Crock, director of the UVM Consulting Archaeology program, said that he was reluctant to take up the Hartland job in the first place because of the controversy surrounding the cemetery. He said that it was presented to him by Guite as something that was going to be done either way, and he wanted to get involved “to do it right.” The UVM team received more than $70,000 for their work.

Les Motschman, a Hartland resident and treasurer of the historical society, said given the extent of the report and the work to create a new cemetery for the Aldrich family, it was clear a lot of effort went into the project.”

“Obviously, Mr. Guite spared no expense, so I think you have to hand it to him,” Motschman said. “It’s been a very controversial thing, and some people would try to do it at the least expense to just get it out of here,” he said.

Motschman described the new burial site as one meant to resemble an “old New England cemetery,” but there was just one thing giving away its true age: the grave markers.

“Except it doesn’t look like New England,” said Motschman, “Because it’s not native stone.”

“Harold Rugg was a Vermonter, scholar and world traveler. He died in 1957 and bequeathed his extensive and significant collection of Vermontiana to the Vermont Historical Society.”

The Vermont Historical Society has Mr. Rugg’s collection on display, but also has a lot of pictures and other information about the collection on their website.

The circumference of strawberries in P. B. SMITH’s garden is, or was Monday, 4 3/8 inches.

Melvin J. HOLT returned home from the west, Tuesday.

H. R. WATRISS and D. P. ATWOOD, Four Corners, had green peas Sunday, the 22nd.

Charles G. BURNHAM is confined to the house with rheumatism. a very severe attack.

The remains of Oliver HAYES, who died in Lebanon, N. H., were brought here, where he formerly resided and deposited in the old burying ground on the plain.

A. A. MARTIN has entered suit against the town for the loss of a horse June 19, ‘83, the same having been killed by running off a bridge near Martin & Stickney’s mill in consequence of alleged unsuitable protection against liabilities.

Dana P. ATWOOD has made the village at the Four Corners look better, and greatly improved the value of his property, by newly painting and blinding his house. The work was done by Paschal P. WATERS, and is well done.

Waldo & Dickinson’s block has been thoroughly painted and the appearance of the building, about sixty feet long, and the street are greatly improved thereby.

Frank GILBERT, at his foundry, is casting (one each day) eight columns for a new block in Montpelier. The weight of each column is 1,000 pounds.

E. S. AINSWORTH, administrator, held a recent sale of property belonging to the estate of Phelps HUNT, at the Four Corners, N. W. PATRICK auctioner. The sale was held within a few yards of the old PATRICK home where Norman commenced, and afterwards completed in the old union store of Windsor, under M. C. HUBBARD, the development of that wonderful linguistical talent which has since made his name famous wherever goods of uncertain value were to be disposed of to the best advantage.

Having twenty minutes spare time at the railroad station, a few days since, we called on Mrs. Ralph LARABEE to inspect a silk bed quilt made by her, of which we had previously heard, and were well repaid for the time spent. The quilt is of the log cabin pattern and contains 4,000 pieces, and is one of those rare specimens of art which only the few are capable of producing. If any intensely practical soul, who would see more beauty in a bushel of potatoes than in anything wherein ornamentation and use were combined, should call this a waste of time, we should answer that Mrs. LARABEE is an invalid, and has done the work while nearly every one in her condition would have done nothing.

Delegates to the republican county convention at Woodstock this week, James G. BATES, George WILLIAMS, W. T. RICHARDSON, Wilson BRITTON.

Rye from the farm of J. C. HOLT, this week, measures 6 feet 8 inches. Later. Sorry for friend HOLT, but just as the foregoing was written, the door of the newsroom opened and O. H. HEMENWAY came in with specimens of the grain measuring 8 feet.

Something like twenty-five years ago, Charles W. WARREN laid a cement foundation in the old tan yard at Foundryville. Being laid in direct contact with the soil, newspapers were spread out on the ground to prevent the moisture being absorbed too quickly from the cement, which would interfere with the process of “setting.” Since the tanyard was burned the property has come into the hands of Frank GILBERT, and the cement bed has been broken up. The other day, while among the ruins, we found a portion of an old VERMONT JOURNAL completely turned to stone, on which the reading is nearly as legible, and the color of the paper nearly as white,as it was the day it was printed.

There was quite a large delegation from this town to witness the graduation exercises of the Windsor High School, last week, among whom may be named Mr. and Mrs. M. C. HARLOW and daughter, Mrs. O. W. WALDO, Mrs. J. G. MORGAN, Mrs. Watson HARDING, Miss Clara A. LAMB, and Mrs. Harland NEWS.

Byron P. RUGGLES has drawn in chalk, on the end of his calf shed, fronting the road, profiles of the republican nominees for president and vice-president, with the announcement: “Now we have James G. BLAINE.” Four years ago the names and profiles of Garfield & Arthur appeared on the same bulletin board, and are still partially visible.

The graduating exercises of Kimball Union Academy, Meriden, N.H., were held last week Thursday, and were attended by several from this town, including Mr. Wm. PERRY and Mr. and Mrs. J. H. EMERSON. The salutatory address was by Miss Carrie E. PERRY, of this town, and is spoken of as a very fine production.

Mr. and Mrs. Carlos McGREGOR have settled their differences, whatever they may have been, and are established in their home on Densmore Hill.

It is so long since the ninepences and fourpences were in general circulation that one dug up the other day by “Jop” REED, in the Pavilion Hotel garden was sent to one of the coin collectors here to find out what it was. It is a very perfect specimen, and dated 1781.

School closed June 17–whole number of pupils 18; those neither absent nor tardy were Charles CUSHING, Frank CARPENTER, Lucy FLOWERS, Don FLOWERS, Ahira FLOWERS, Annie THAYER. Those having no absences, and but one tardy mark, were Carrie DAVIS, Eva DAVIS, Howard GILSON. Those having no tardy marks, and but one absence were Frank CARPENTER and Cora SMALL. Closed with recitations by Lucy FLOWERS, Ismay ATWOOD, Carrie DAVIS, Eva DAVIS, Cora SMALL, Annie THAYER, Ahira FLOWERS. Ernest ENGLISH, Frank BILLINGS, Fred CARPENTER, Frank CARPENTER, Don FLOWERS and Elisha FLOWERS. The pupils never made better progress than during the term just closed, which has been taught by Miss Louise M. BATES.

Transcribed by Ruth Barton