In November 1913 as Hartland, Vermont was celebrating its 150th anniversary, The Vermonter magazine published an article by Nancy Darling entitled, “History and Anniversary of Hartland”. The following is a transcribed version of that article.

History and Anniversary of Hartland

By NANCY DARLINGFrom the day when Gov. Benning Wentworth of New Hampshire granted the first charter to Hertford (now Hartland), Vt. July 10, 1761, until the ushering in of the twentieth century, the town had never officially turned a retrospective page. Its history had been one continuous tale of action – the pioneer’s, the soldier’s, the legislator’s, the home-makers.

But in 1901 Hartland voted to observe as an “old home week” August 11-17. Hundreds returned to the beautiful old town and brought a key to the past that can never be lost. This year it was voted that another old home wee be set apart for the s pecial observance of the one-hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary of the town’s settlement.

Before reviewing the literary program, the exhibit, and the street parade arranged by a committee for the principal day, Aug. 16, 1913, it will make the reading clearer to note a few of the local events that have occurred during the past century and a half.

According to record, the first English name given to that territory west of the Connecticut River of which Hartland forms a part was “Laconia,” the charter name of Charles I’s grant to Capt. John Mason and Sir Ferdinando Gorges in 1622, under the jurisdiction of Massachusetts. Laconia, as Sir Ferdinando dreamed it, was to be a great kingdom, and the glorious banner of his family was to gather beneath its folds, both Cavaliers of the Church of England and Puritan Dissenters. The second name was “New Hampshire,” employed in the charter issued to Capt. Mason in 1629. This held until after 1749, when Benning Wentworth, Governor of the Province of New Hampshire, began to make concessions of lands west of the Connecticut River to persons wishing to settle there. Towns chartered by Gov. Wentworth soon became known as “New Hampshire Grants,” and these, repatented by New York almost immediately, were often referred to as “The New York Claims.”

Just when the first white man visited the region now called Hartland none can say; but, in 1704, a band of French and Indians traversed it on their way to and from Deerfield, Mass. As the eastern limits of the territory bordered the Connecticut River, it was a natural thoroughfare for both red men and white previous to the time of highways.

Old residents of Hartland have told the author about the Indians who formerly visited the Waterquechee Falls, now called Sumner’s, to listen to the roar of the waters and the sighing of the pines as the sounds echoed to them from Home Mt. in New Hampshire opposite, and how it was believed that the Great Spirit dwelt upon that mountain, where they held their councils and signaled by fire in the days of their undisturbed possession. At the base of Home Mt., south of the falls and near the river, is an Indian burying-ground, some say, where arrow-heads were gathered by the pioneers. A descendant of one of the first settlers near these falls tells of the tricks one of the white men of Hartland played, as: When the Indians came to sell their furs, this man would say that his foot weighed a certain amount and then balance the furs with his foot as it pleased him, and that, on being asked by the Indians how he obtained gunpowder, he told them that he planted it, and they buying some and planting but receiving no crops therefrom, became mightily incensed against him – so much so that he fled for his life.

At the close of the French and Indian War, some of the red men returned to Hartland to live with their families. There was a settlement of Indians at North Hartland, according to the late Mr. Paul Richardson, that was destroyed by the whites and whose chief turned and cursed the invaders of the place he was fleeing. Evidences of a settlement exist in the vicinity of the John Webster farm, where arrowheads have been found and a spherical stone a foot in diameter supposed to have been used for grinding corn and in crushing paint from a bed that is near. Mr. Daniel Webster has the stone now.

Indians formerly wintered near Fieldsville, and several persons living have heard the following tradition about one of them: Not long after the settlement of Hartland, an Indian used to pass annually through Fieldsville inquiring for a man by the name of Smith, and it was learned that “Capt.” Samuel Smith, who was born in 1757 and who served as one of Washington’s bodyguard, had, as an unthinking youth, come upon an Indian Papoose while out reconnoitering with other Minute Men near Bellows Falls. Carrying the babe up the river, they set it down near Waterquechee Falls, where it was found by the pursuing parents. The Indians learned that Smith was the culprit, and from that day sought to wreak their vengeance upon him. He made a home on “Smith Hill” in the “Weed District,” raising a family there, and so far as known, was never molested.

Miss Clarine Gallup remembers that when some Indians camped in the woods to the east, near the F. G. Spear place, a squaw named “Sophie Soisine” would come to her father’s house to sell baskets and ask for salt, and Mrs. T.A. Kneen recalls very vividly how, when she was a small child, a band of Indians dressed in buckskin filed into the great kitchen to the number of twelve or so and asked her father, Mr. Benjamin Carey, who lived on what had been the George Marsh place at the western limits of the town, if they might stay over night, and how they arranged themselves on the floor in a semi-circle with their feet to the fireplace, while her father, when he went up stairs to bed, placed an axe beside the door of his sleeping room. Until about the middle of the last century, there lived, on that part of the Carey farm now known as the “Eshqua Bog,” a squaw and her papoose, in a bark wigwam covered with hemlock boughs. Mr. C. E. Darling of Hartland remembers her, and Dr. S.E. Darling of Hardwick, Vt., remembers hearing his father tell of seeing the brave who lived with her. She used to weave ash baskets to sell to the neighbors and was always pleased to have people say a good word for her little one.

“Everyone love my baby” she would answer smilingly to the compliments.

Near the Burk schoolhouse at the Four Corners, and Indian hatchet was ploughed up by Mr. George Jenne; while Mr. A. J. Stevens has several arrow points, an iron needle made for sewing skins, some grinding stones, and other things picked up by the spring on the Isaac Stevens land. The Indians liked the water of this spring especially well, and some of their families lived near it. Mr. Joseph Livermore, who came to Hartland with his father in 1797, used to tell of some Indians, two in particular, that would cross over near his home to a pine ridge and return with lead ore that was nearly pure from which they made bullets in those days.

On the Isaac Stevens plantation, which included at one time about 1800 acres, both silver and gold, as well as the lead which the Indians used, have been reported as found in small quantities.

In certain nearby towns refuge cellars were built in the fields to afford protection against the savages in cases of raids; but the author knows of only one cellar in Hartland that might have been used as such. It is firmly walled, roofed by a great stone slab, and would shelter half a dozen persons. This cellar is on the old James Dennison or D.F. Morgan place in “District No. 9,” and is very near “Sky Farm.”

Hartland Minute Men were called upon several times to go to the relief of places attacked by Indians – Bernard, Royalton, etc.; but, in those cases, the Indians were mostly from Canada. The local bands gave very little trouble, being remembered with friendliness rather than with fear. William Symes Ashley, Asa Wright, and Moses Webster are the soldiers that went to Barnard, and Hartland rewarded them in money, as is shown by an entry in the town clerk’s book for 1780 – Voted “ * * that we will ensure to three Soldiers their pay of 20s pr month.”

At the time when Gov. Wentworth gave the charter, Hartland was an unbroken wilderness. Probably no white man had then cultivated its soil, though two years later Timothy Lull found a log cabin on Lull Brook sufficiently livable for himself and his family. The “Plantation:” of Hertford was granted by the “Trusty and Well-beloved Benning Wentworth” in the name of George the Third, “By the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, etc., etc.” to “our Loving Subjects and Inhabitants of Our said Province of New Hampshire, etc.” – to be divided to and amongst them into Seventy-one equal Shares.” The names of the grantees of Hertford in the New Hampshire charter are:

Samuel Hunt, Ebenezer Harvey, Thomas Chamberlain, Benjamin Taylor, Andrew Gardner, Andrew Powers, Joseph Lord, Joseph Willard, Enoch Hall, John Hunt, John Hubbard, Jacob Foul, Thomas Taylor, Aaron Hosmorre, John Hastings Junr., Jonathan Hunt, William Symonds, William Nutting, Samuel Minot, Moses Wright, Wilder Willard, Caleb Strong, Sampson Willard, Phineas Waite, Lucius Dolitle, Zadcock Wright, Thomas Chamberlain Junr., Michael Gellson, Levi Willard, Elisha Harding, William Willard, Amasa Wright, Daniel Shattuck, Amos Tute, Joseph Burt, Nathan Willard, Uriah Morse, John Harwood, Daniel Sargent, Willard, Stevens, Fairbanks Moore, James Nevin Esq., Wm. Moulton, Wm Earle Treadwell, George March, Benning Wentworth, Timothy Porter, Oliver WIllard, Howard Henderson, Samll Wentworth, Boston, Clement March Esq., George Waldron, John Trasker Esq., Ebenezr Hinsdale, Elisha Hunt, Nathaniel Foulsom, Jonathan Blanchard, Richard Wibird Esq., Elizr Russell, Henry Hilton, John Goffe Esq., Majr. John Wentworth.

The shares included two for “His Exellency,” or 500A.; one for the “Incorporated Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts;” one, for a “Glebe for the Church of England;”

one for the “first Settled Minister of the Gospel,” and one for the “Benefit of A School in Said Town.”

The first town Meeting, or meeting of the “Proprietors,” provided for by the charter, ****Can’t read bottom of left and right columns of page 223.*** grantee, of whom there were sixty-five, his heirs, or assigns, was to cultivate five acres out of every fifty during the first five years. All pine trees fit for masting the royal navy were to be preserved and non such cut without special license. A tract of land near the centre of the town was to be marked out for town lots, one acre to each grantee, and the rent was to be, for each lot, one ear of Indian corn paid each year on Christmas day for ten years, if demanded. After ten years, one shilling was to be paid for each hundred acres owned, settled, or possessed “yearly and for every Year forever.”

As soon as there were fifty families, “resident and settled,” the townspeople were to be allowed two fairs annually and a market “opened and kept one or more Days in each Week.”

A drawing of the map which accompanied the charter shows that Benning Wentworth’s lot was in the north-eastern corner ****Can’t read bottom of left and right columns of page 223.***

forming a square. A part of this land is now in the possession of Mr. Howard Miller of North Hartland and is always referred to as “The Governor’s Meadow.”

The lot for the propagation of the gospel in foreign parts was in the south-western part of the town near Hon. Henry Walker’s farm at South Woodstock. The following list shows the names of those taxed by the Episcopal Church in early days and in the present year on lands leased them by the “Propagation Society:”

Alfred Bell novo Mrs. Oliver Kingsley

Oliver Bailey novo Mrs. Oliver Kingsley

Samuel Weeden novo Mrs. Oliver Kingsley

Amos Ralph novo Ralph Jaquith

Oliver Bailey novo Mrs. A. P. Dinsmore

Holt. Ralph H. Slayton novo Julius Gamling

Henry Rood novo M. J. Holt

The taxes are paid to Mr. Frederick Chapman of Woodstock. The glebe is leased in sections for school purposes, and the following Hartland persons pay school taxes on them this year to the town treasurer: Mrs. A. L. Dunsmoor, John D. Rogers, Martha Crandall, O. C. Watson, E. A. Kinsley, and Frank Sawyer.

No church was built in accordance with the plans of the N. H. charter. The proprietor’s map shows that school land was to be reserved on “The Plain,” and there a schoolhouse may have been built; for, in 1789, the town clerk used this phrase, “at the notch of the road in the south part of the town where the schoolhouse was formerly built.”

It is probable that Oliver Willard notified the proprietors of the first meeting in August, 1761, as provided by the charter; for his warning of a similar meeting in 1763, the oldest document, except perhaps the map, among the records of Hartland, implies previous meetings.

The warning reads:

“Province of New Hampshire, february ye 21st, 1763 — Whereas aplication hath this Day been made to me the Subscriber Clerk of the Proprietors of Hertford By more than one Sixteenth part of the Proprietors of the Said township Desiring me to notify and call a meeting of the aforesaid proprietors to meet at the Dwelling house of Capt. Oliver Willard In Hertford In the aforesaid province on the fifteenth day of March next which day Is our annual meeting and to meet at one O’clock In the afternoon To act and vote on the following articles – viz. – 1st to chose a moderator 2ly to chose a Proprietor’s Clerk 3dly to Se Iff the proprietors wil Raise a sum of money for to defray the charge of making of Roads and other contingent charges that Shall or may arise In said town 4thly to chuse assessors to assess the Same 5thly to chuse a collector 6thly to chuse a treasurer 7thly to chuse a committee to Settle accounts with the Clark treasurer and Collector and pass accounts 8thly to Se If they will buy a proprietor’s Book 9thly to chuse a committey to lay out roads In said town and to git them made. This is to notify the Proprietors of Hertford To meet at time and place above mentioned.

Ovr Willard propr Clerk”

On the back of the paper is the title – “Notification Hertford, February 21, 1763.”

The law then requiring that there be settlers owning land in a town sufficient to equal one-sixteenth of the number of shares granted before a meeting of the proprietors be held in that town, it follows from the above warning that there were in February 1763, at least four actual settlers within the limits of Hertford. Oliver Willard himself is known to have come to Hartland to live in 1763. He had a house at North Hartland where a meeting could be held as early as the date of the notification, – all of which disturbs the ordinary statement that Timothy Lull, the first settler, came to Hartland in May, 1763. It has always been said that he came with his family in May, 1763, and the tradition is persistent that he was the first settler. The conclusion is therefore that he came a year or two earlier, without his family, and waited for witnesses to the christening of Lull Brook and the breaking of the famous flask as they entered the mouth of the stream in a canoe. Mr. B. P. Ruggles, the antiquarian, has copied a statement that illuminates this question, from Timothy Lull’s tombstone in the cemetery on “The Plain.” It is contained in the inscription and reads, “He was the first settler on Connecticut River above Charlestown No. 4.”

Another quotation, sent by Mr. H. G. Rugg of Hanover, N. H. confirms this. It is taken from The Washingtonian (Windsor, Vt.)

Monday, September 16, 1811.

Died, – At Hartland, on Tuesday last, Capt. Timothy Lull, aged 81. He was an industrious, enterprising, worthy citizen, and the first settler on Connecticut River, between Charlestown (No. 4) and the upper Coos. He has left a numerous and respectable family of children, grand-children, and great-grand-children, amounting in all to 103, to lament his loss.

If tombstones may be believed, there was another settler in Hartland in 1762. Mr. George M. Rood, one of the selectmen of Woodstock and a relative of the pioneer, sends the following inscription from his tombstone: “In memory of Mr. Thomas Park Rood, who died October 10th A.D. 1795 Aged 63 years. He moved to Hartland in 1762, one of the first settlers, bore the brunt of a new, uncultivated wilderness, lived to see five of his tender offspring taken by death, one only left to set this stone.

Behold and see as you pass by,

As you are now so once was I,

As I am now so you must be;

Prepare yourself to follow me.

Mr. G. M. Rood adds this note, “The house now standing on the Old Thomas Park Rood farm was built by Thomas, son of Henry Rood, in 1797. The barn was built by Thomas Park Rood, is 44×44 feet square and all Red Elm timber and not a spliced stick in it. The first house on the farm was a log one built on the south side of the road that runs through the land and built by Thomas Park Rood, probably the same year he came to Hartland.”

Col. Oliver Willard’s name does honor to the list of Hartland’s pioneers, for he was a lawyer of distinguished abilities, a large land-owner, and a man of influence among the statesman of his day. He was descended from celebrated ancestors, his grandfather having been Major Simon Willard, the “Indian Fighter,” who came to New England in 1634, and his father, Col. Josiah Willard of Fort Dummer.

On the original proprietors’ map are some lots marked near the North Hartland section with the names – Spooner, Hunt, Richardson, Lee, and Taylor, and it may be that some of these men took up ladn as soon as the charter was granted in 1761. On the map copied from the aforesaid by Caleb Willard in 1789, four lots are marked in the North Hartland section and named – “No. 1, Uriah Morss;” “No. 2, William Willard;” “No. 3, — Wait;” and “No. 4, Nathll Fulsom.”

The King’s pines in Hartland were of great value, covering as they did “The Plains” and a large portion of North Hartland. One of them is still standing behind Mr. Daniel Webster’s house. A timber in this house made from one of the royal pines is 8 in. square and 55 ft. long, and it was 62 ft. long before being cut off. Mr. C. C. Spalding says that on the Frank Whittaker place at North Hartland are red pine rails, still sound, that were split on the day of the Battle of Bnker Hill.

It is proabale that the “Center of the Town” was never marked out for one acre, lots; and as to the paying of a yearly rent of Indian corn at Christmas and having “two fairs and a market,” no one living in Hartland ever heard so much as a suggestion of them.

The long controversy that arose respecting the “New York Claims” is admirably set forth in an address by the Hon. Gilbert A. Davis given at Hartland’s recent celebration and published at Windsor, Vt. in a pamphlet styled “Hartland Anniversary, Aug. 15, 1913,” and is therefore omitted from this sketch, which aims to include unpublished matter mainly.

Doubtless the reason for Hertford’s having so little serious trouble with New York lay in the fact that Col. Oliver Willard was in great favor with that state; therefore the New Hampshire charter, in which he had been a grantee and had appointed moderator for the proprietors’ first meeting, was readily confirmed by New York and was recorded in the auditor-general’s office July 25, 1766. The New York charter was granted by Gov. Cadwallader Colden to Oliver Willard and his associates – Samuel Hunt, Joseph Willard, Zur Evans, William Syms, Zadock Wright, Amasa Wright, Lucius Dolittle, Jonathan Hunt, John Laiton, Experience Davis, Thankfull Willard, Daniel Goldsmith, Obadiah Wells, George Hopson, Henry Beekman, John De Peyster, Junior, John Stout, Benjamin Stout, James Wessek, Joel Matthews, James Harwood, Thomas Taylor, John Hastings, Junior, and John Stevens. “All this aforesaid large Tract or parcel of Land set out, abutted, bounded, and described by our said Commissioners in Manner and form as above mentioned. Except the said Tract of Land (100 A. from the southern end of Hart Island north, etc.) granted to the said (Lieut.) Thomas Etherington as aforesaid, but including all the afore mentioned several smaller Tracts or Lots of Land set out and described by our said Commissioners as parts and parcels thereof containing in the whole Twenty-four Thousand two Hundred Acres of Land besides the usual Allowance for Highways.”

Further exceptions were made of “All Mines of Gold and Silver;” but, in the main, the grant was much like that of Gov. Wentworth. The number of acres mentioned in the first charter is 26,000; but surveys and the setting off of a portion to Hartford in running the line has reduced the acreage.

In the Hartland records, which are full and perfectly legible from the earliest days to the present, Oliver Willard appears as moderator of the first town meeting, March 19, 1767, and as the first formally elected town clerk March 19, 1769. This is a list of the town clerks up to the present: Oliver Willard, 1769; William Symes, 1770; Joel Matthews, 1771-72; Zadock Wright, 1773-76; Paul Spooner, 1777-80; Elias Weld, 1781-89; Oliver Gallup, 1790-96; Stephen Maine, 1797; Marston Cabot, 1798; Daniel Breck, 1799-1812; Eliakim Spooner, 1813-16; Daniel Ashley, 1817-19; Ira Person, 1820-21; Daniel Ashley, 1822-27; Sylvester Marcy, 1828-30; Theophilus Hait, 1831; John S. Marcy, 1832-35; David W. Wells, 1836; Dustin Bates, 1837; Eben M. Stocker, 1838-54; Henry Shedd, 1855; John Colby, 1856-57; Albert B. Burk 1858-77; Wilber R. Sturevant 1878-1913.

Early town meetings were held at various places, at William Gallup’s in the northern part of the town, Isaac Steven’s hotel at what is now Hartland, Joseph Grow’s house at the centre of the town, the old union meeting house, etc. Later meetings were held in the basement of the Methodist church and finally in the arsenal at the Four Corners, where they are still held. The town clerk’s office has generally been either at his home or his place of business.

Mr Sturtevant, the present clerk, has indexed the books, including the land records.

Oliver Willard having secured Hertford’s rights temporarily, proceeded to buy out the grantees by two separate transactions, which conveyed the whole town practically to him. He then continued the settlers in their holdings and deeded a tract of 8,200 acres in the south-western part of town to William Smith, Jr., Thomas Smith, Whitehead Hicks, and Nicholas William Stuyvesant, all prominent in New York City, for £800 or about $4,000. These four men purchased for speculation simply; but the lands of Whitehead Hicks and Nicholas William Stuyvesant were confiscated “for treasonable conduct in joining with our enemies.” William Smith, who became Chief Justice of Quebec and who had deeded lands to the pioneers, transferred his share of 2,000 acres to Benaja Child of Pomfret, who, in tern, made a satisfactory agreement with the following settlers in 1789: Samuel Healey, Ebenezer Holbrook, Samuel Williams, Timothy Grow, Ebenezer Allen, Jesse Peek, Joseph Marsh, and Melvin Cotton. The Smiths are always referred to with respect.

The years following immediately upon Vermont’s declaration of independence, in 1777, were years of settlement in Hertford, 1778 being the date of the first deeds recorded in the “First Book of Deeds.” Meantime the town was contributing an active share in resisting the invasion of savages, in applying the laws of the new state, and in drilling, arming and fighting against New York presumption and British tyranny. In 1778 the “Green Mountain Boys” were organized, and probably nearly all of Hertford’s able-bodied men were among them, beside those already officers.

Even Quakers – or Friends – served in the Revolution, either here or elsewhere. These were excused from paying church taxes in Hartland and allowed to continue attending church in Woodstock in 1790. “As to the denomination called friends,” to quote from the town records, these were the names affixed to the release: Robert Anderson, Abner Brigham, Samuel Healy, Ebenr Paine, Ebenr Allyn, Joseph Marsh, Daniel Marsh, Roger Marsh, Seth Darling, William Anderson, Joseph Anderson, Abel Marsh, Roger Marsh, Benjn Marble, James N. Willard, Seta (?) Russell, Isiah Aldrich.

Among the active founders of the state of Vermont was Dr. Paul Spooner of Hartland. He was appointed clerk of the Cumberland County Convention Feb. 7, 1774, and, at that time, he, Esq. Burch and Jonathan Burk, all Hertford men, were voted as a “Standing Committee of Correspondence to Correspond with the Committee of Correspondence for the City of New York.” Paul Spooner helped to voice a protest against British taxation Oct. 19 1774, at Westminster, and when the Cumberland County Congress assumed the duties of a Committee of Safety, Nov. 21, 1775, Dr. Paul Spooner of Hertford and Major William Williams were chosen to represent the people of Cumberland (which included the present Windsor County) “in the honorable Provincial Congress, at the city of New York.” At the November meeting, Capt. Joel Matthews of Hertford was recommended to be commissioned “Second Major of the Upper Regiment.” He received the commission.

Dr. Spooner was re-elected as delegate to Congress, chosen sheriff of Cumberland County, was made deputy-secretary of the famous Vermont Council of Safety, and was one of those that signed the Constitution of Vermont, at the Windsor Convention, July 2-8, 1777. He was a member of the Governor’s Council for the new state until he was elected Lieutenant Governor, and was a judge of the Supreme Court of Vermont for many years.

Major Joel Matthews and Mr. William Gallup of Hertford were among the members that adopted the Constitution, and they had been among those who signed the revised Declaration of Rights. William Gallup, styled “Col.” on an old Hartland Map, was one of the members of the Convention that met at Dorset, Westminster, and Windsor. He assisted in framing the state Constitution, and was for a long time a member of the Legislature. Both he and Lieut. Gov. Spooner died in Hartland, and there they are buried. Jonathan Burk of Hertford was a member of the Committee of Safety and attended several of its meetings, but non of these following the formation of the state.

Hertford disapproved of including the New Hampshire towns east of the Connecticut River as part of the state of Vermont. There was a powerful coterie of political and military leaders in Hertford during the Revolution – one that would attract the attention of young Vermonters, if the truly great work which they did so modestly were understood. Paul Spooner, William Gallup, his son Oliver, and Col. Oliver Willard were jurists.

Mr. Dennis Flower’s brochure on “Hartland in the Revolutionary War” records a large number of soldiers sent forth by the town and names several officers who lived at North Hartland. Toward the close of those troublous times, Major General Roger Enos, while commanding all the military forces in Vermont from 1781 to 1791, lived in North Hartland. (The name of the town was changed from Hertford to Hartland in June, 1782.) Further, the house which he built, known as the “George Miller House” still stands near the Ferry.

The “Haldimand Correspondence” was well understood by General Enos, also probably by other Hartland men, and every permissible turn of diplomacy was employed to keep Britain at bay on the Canadian border while negotiations were pending for the admission of Vermont to statehood. General Enos was made a Freeman of Vermont in Hartland, and the clerk’s entry reads, “At a meeting of the Freemen of the Town of Hartland Septr the — 1782 General Roger Enos Took the Oath provided for the Freeman of the State of Vermont. Attest by Elias Weld Town Clerk.”

He was an Episcopalian, and with Maj. Gen. Benjamin Wait of Windsor, was influential in having the church of that faith built at North Hartland about 1790. This is now the oldest church in town.

General Enos represented Hartland in the General Assembly several times, while he was frequently moderator of meetings in his own town. The records show him as moderator of a meeting March 28, 1782, where it was voted to “Divide said Inhabitants into five Classes to raise the five Men Required for the Ensuing Campaign;” also at another, May 3, 1785, where “Mr. William Gallup was chosen to attend on a Committee * * * to Affix on a place for the County Public Buildings,” and where Mr. William Gallup and General Roger Enos were chosen by ballot as “Agents to attend the General Assembly to pursue a request to said Assembly to Establish New York Charter in said Town of Hartland.” General Enos was moderator when the selectman laid before the townspeople “the preambilating of the Line between the Town of Windsor & the Town of Hartland as performed November, the Twenty-first and Twenty-second past (1786).” (The line between Hartland and Hartford was run in 1778.)

At one of the meetings over which the General presided, Nov. 19, 1787, “It was proposed to Choose a Comtt to see how the Ammunition was disposed of that was delivered to Capt. Aaron Willard and others in the year 1777,” and the vote passed in the affirmative. Then it was voted that “the Selectmen of said Town and their Successors in office be appointed * * to look up the Ministry right and the School right (Episcopalian or Church of England);” also that the town be divided into school districts.

On Dec. 3, 1778, as the entry is in the records, a division of the town was made into nine (9) school districts – probably the first division, the account of which, with early names, is very interesting. Many years later the number of pupils in the following districts was reported thus: Districts: No. 1, 1803-77; No. 2, 1802-113; No. 3, (omitted always); No. 4, 1807-66; No. 5, 1801-54; No. 6, 1801-65; No. 7, 1803-49; No. 8, 1802-64; No. 9, 1803-56; No. 10, 1801-76; No. 11, 1802-40; No. 12, 1803-57; No. 14, 1803-40; No. 15, 1803-13; No. 16, 1802-24; No. 17, (reported for the first time), 1811-21; etc. In 1790 the number of pupils in Dist. No. 5 (North Hartland) was 90.

At the same meeting where the division of the town into school districts was decided, Dec. 3, 1778, it was voted to raise a tax of “one penny on the pound * * in Money or Wheat at three shillings the Bushel to defray the costs of charge against sd Town for Ammunition procured for the aforesaid Town by Capt. Abel Marsh of Hartford.”

Little is known in general about Revolutionary preparations in this section; but the common around the “Union Meeting House” at the centre of the town was one place where the “Minute Men” trained. Nor are there reminiscences of any moment about these brave

“Green Mountain Boys” At North Hartland, it is said that the mother of two sons who were at the Battle of Bunker Hill heard the roar of conflict there, and it is thought that she was Mrs. Evans, the mother of Joseph and Moses Evans, who were at the famous battle.

One officer, Liut. Samuel Bugbee, was retired by the town Sept. 7, 1790. Several soldiers who were with Gen. Stark at the Battle of Bennington rest in Hartland graves, and the best inscription on any soldier’s tombstone is that of Gardner Marcy, who lived in Fieldsville, Hartland and built the Colonial mansion from which Mr. Maxwell Evarts of Windsor obtained a rare fireplace. The inscription reads:

Gardner Marcy EsqBorn in Woodstock, Ct. 1837-75 In early life a patriot and defender of his country. Revered in his public and private stations : as a friend, true and faithful : as a husband, affectionately kind : as a parent, tender and beloved : as a man, honest.

There are nine grandsons and granddaughters of the Revolution living in Hartland, all descended from Hartland men: Grandsons: Messrs. Wm. J. Allen, Wm. W. Bagley, J. F. Colston, Charles E. Darling, Elbridge Gates, Albert E. Gilson, H. A. Gilson, L. J. M. Marcy, and Andrew J. Stevens; Granddaughters: Madames Louise Bugbee, Rosaline (Flower) Clifford, Adelaide Crosby, Eliza Shattuck, Frances M. Spear, Adaline Sturtevant, Louise M. Sturtevant, Mary A. (Hodgman) Thayer, and Miss Clarine Gallup.

There has been much discussion over the date of the building of the church at the centre of the town. Mr. W. R. Sturtevant thinks it was 1780. The author finds no exact statement to that effect, but references would confirm the date. For instance: In 1779 a committee was appointed by the town to “to fix a place for a meeting House spot,” and “The Centre” was chosen; also, “three acres of land or thereabouts” were accepted from Mr. Bugbee for a common. In that year it was voted to hire Mr. Martin Tuller “on Probation ten Sabbaths more and to pay him twenty shillings per day the old way,” the meeting places to be at Dr. Spooner’s barn and Col. Symes’ barn.

The Rev. Daniel Breck, who served as chaplain in the Continental Army and who has always been called the first “settled minister,” was living in Hertford in 1779, as is proven by the tax-list passed in to Mr. Elisha Gallup, the collector. It is written in Daniel Breck’s own hand and reads —

Hartland th 20 79 to

1 Pole 6 - 0

1 Horse 4 - 0

1 yeerling Colt 1 - 0

3 Cows 6 - 0

2'2 yeer olds 2 - 0

2 yeerlings 1 - 10

28 acres improved land 14 - 0

-------

A true list, £35 - 0

Daniel Breck

From the heading of this list, it would seem that the name “Hartland” was used before it was formally authorized in 1782.

Daniel Breck’s list suggests another, too good to be omitted, though it in no way concerns the church. It is:

“Capt.” Samuel Smith belonged to the “Troops of the Line” and served as one of Washington’s Life Guard on the Hudson after the attempts were made to capture the great patriot.

The church at the centre of the town was Congregational largely at first, and its oldest book begins: “Hertford 6 September 1779. This day the Church of Christ was gathered here in the presence of the Reverend Isiah Potter, David Tuller, and Pelantiah Chapin & Chose Elias Weld Moderator & Clerk. Members – Joseph Grow, Elias Weld, John Hendrick, Samuel Abbott, Zebulon Lee, George Back, Joseph Grow Junr, Abijah Lull, Hannah Hendrick, Rhoda Capen.”

Thus it is shown that a church spiritual existed in Hertford as early as 1779. Dec. 26, 1780, the town voted a salary to Mr. Nathaniel Merril of £30 annually the first three years, also “to set up a Dwelling House about 28 ft. square, one story, fine boards, clapboards and shingles.”

This may have been the one room in which Ebenezer Cotton, the choirmaster, lived later, with its chimney built outside and its Cotton children within named after all the letters of the alphabet.

At the town meeting held the first Tuesday in Sept., 1789, it was voted “to give the Rev. Daniel Breck a call to the work of the ministry in this town.” He accepted, and lived the remainder of his days, until 1838, in Hartland. Graven on his tombstone are the words – Mark the perfect man and behold the upright for the end of that man is peace.

Mrs. Adaline Sturtevant, ninety years of age, has always lived in Daniel Breck’s neighborhood, and Mrs Phylura (Harlow) Bond, now ninety-one years of age, knew Elder Breck and his family well. She says that “Rev. Father Breck” always wore at home a long black gown with scarlet facings. She remembers his children by the names – Samuel, Daniel, Hannah, Abba, Dolly, and Lucy. Elder Breck always drove about in a chaise.

It seems from the following paper of the Moses Webster collection that Pomfret’s revered missionary to the pioneers came to Hartland:

Received six shillings and eight pence of Moses Webster toward Mr. Aaron Hutchinson preaching last summer.

March 24, 1784 Paul Spooner.

In early days, Hartland was always reporting the laying out of roads, and there were, at least three named roads – the “Old Post Road” on the Connecticut River, of which there is a map; the “County Road,” from Windsor to Woodstock over the hills and passing through Fieldsville, and the “Windsor and Woodstock Turnpike,” which had two toll-gates – one near the Goodwin place and the other near the Hemenway place.

Readers may take an interest in a glimpse of an early family through this letter sent by Mrs. Jerome H. Eastman and written by Mrs. Jennie (Brown) Smith.

My Grandfather (Solomon Brown) brought his bride from Connecticut on a famous saddle horse, giving ease of motion to the rider, being sure-footed and most tough and enduring – the bride rode on a pillion – a padded cushion which had a platform stirrup. They brought all their household effects along with them in saddlebags; bread, jerked bear’s meat, ham and cheese furnished food for the journey. They could while crossing the State of Massachusetts buy corn of the farmers for their horse but after reaching the wild woods of Vermont they could find but little for their horse to eat so let him browse. Some of the way there was no path, the way was marked by trees a portion of the distance and by sight clearings of brush and thicket for the remainder. No stream was bridged, no hill was graded, and no marsh drained. The path led through woods which bore the mark of centuries and along the banks of streams that the seine had never dragged. Whenever they found a settlement they were always welcome to spend the night, but sometimes darkness closed around them before “they saw the Smoke that so gracefully curled” and the shrieks of the catamount and owl made life hideous. At last they reached Hartland in the spring of 1782. Grandfather came to Vermont with the pioneers in 1780, to clear the land and build a log cabin to make it possible to live amid the wilds of the Green Mountain State. They soon set their house in order and selected a hollow tree near by where they kept their best wearing apparel where it would be safe in case of fire.

In the early afternoon one pleasant July day, grandmother, in petticoat and loose gown, donned her log-cabin sunbonnet and went out to weed her flower bed. Looking up, she saw a young woman emerging through the woods, at the edge of the clearing: she left her flowers at once and ran to meet her; she was carrying in her arms a boy baby eight months old and a girl of three summers was following on behind. The woman was a neighbor, the wife of a settler who was clearing up the farm where Fillmore Benjamin now lives – she was coming to make the young bride a visit, so they spent the afternoon together making plans for the future. They had a 4 o’clock tea; for even in those primitive days, they thought it necessary to be fashionable. The neighbor started for home long before the sun had set behind the woody hills, and grandmother was to accompany her part of the way – when they had gone about half a mile they heard a terrible howling, and looking through the forest they saw two big bears and a cub making dead set at them; they just ran for dear life, and that was all they could do –

bruin soon caught up with them, and grabbing the baby with his savage teeth they soon devoured it while the women and little girl escaped unharmed. Some men near by who were burning logs started for the bears with a shot gun and killed one of them – the other left for parts unknown.

The men “burning logs” might have been doing so to make “salts” or soda, which, with corn, wheat, etc., was used as money. It seems that Spanish “milled dollars” and other denominations were used as current money, also English coins, Colonial, Continental, and State coins and “scrip.”

Hartland has counted many quaint characters among its citizens, but none more picturesque than Hadlock Marcy, Esq., the pioneer. He was born in Woodstock, Ct. in 1739, married a daughter of Rev. Abel Stiles in 1762, and came to Hartland early, where he died in 1821, forty-seven years after his wife passed away. He was a graduate of Yale College and could speak and write seven foreign languages. He was a lawyer and a traveling Baptist preacher, who always rode horseback except on Sundays, when he walked that his horse might rest. His genealogy says: “He was extensively known in Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Vermont.” He always dressed in black silk velvet made in Colonial style, with silver buckles. His grave is in Hartland Hill cemetery.

William Marcy, Esq., was a cousin of Hadlock Marcy’s, the father of Capt. Gardner Marcy, and the ancestor of all the Fieldsville Marcy’s — five different lines of families. In 1778 he came with his family in an ox-cart from Connecticut to Hartland – early enough to find Indian relics on Lull Brook. One that his son Levi found, buried deep in leaves and mould, is now in the possession of his great, great grandson Mr. Jason S. Darling. It is a perfectly preserved buffalo horn used for carrying powder, and is carved with a border of crosses, an Indian bearing a tomahawk and a scalp, and with the name “Mechil.”

William Marcy’s lot adjoined the lot “pitched by Tepe Dunham” before the days of deeds.

In those primitive times, almost every settler built him a log house preliminary to a better one, and Moses Webster, the Revolutionary soldier, is known to have made a bark house before he built his log cabin. One of the oldest fashioned and most curious cottage houses in Hartland is that occupied by Mr. Loreston Woodward, where the Jaquiths used to live, near the “Burk Stand.” It has a wall-bed space built into one side of the parlor, any number of queer cupboards, and is well worth visiting. Mr. H. H. Miller’s old house at the Four Corners is filled with rare Colonial china and other antiques; while Miss Clarine Gallup’s, an ancient farmhouse has perhaps the most varied collection of any in town – manuscripts, books, china, linen, a scarlet cloak, gowns, coats, ornaments, etc.

A very old cottage is that owned by Mr. B. P. Ruggles at Foundryville, long occupied by C. W. Warren. It is said by Mr. Napoleon Luce to be the oldest frame house standing in his day. Its small windows have four tiny panes in the upper portion and nine in the under; its ceilings are very low in the older parts, and its construction is curious. Some think that the Fred White house, built by Samuel Williams in 1782, is older than the Warren house. The Capt. Dodge house, opposite the Mill Gorge, is almost as early as these; while the Lamb house, below, near Windsor, built in 1793, has never been remodeled. The last is filled with rarely beautiful needlework done by Miss Harriet Lamb. The Gen. Roger Enos house at North Hartland must be contemporary with the oldest.

Many early houses show stone “warfings” on which flowers were grown.

Among the fine mansions is “Fairview,” once the home of Lieut. Gov. Spooner and later of Judge Cutts, now owned by the Elisha Gates and Charles C. Gates families. From its verandah, seven towns can be seen across the valley of the Connecticut River.

The “Conant House,” on the plain, was built by James Gilson, a soldier of the Revolution, considerably over a century ago, from bricks made on the ground, after the early custom. Its hand wrought timbers are fastened by wooden pins. The Judge Steele mansion was built by David Sumner, Esq., on the brow of a hill commanding views of river-valley and mountain. In its yard is much shrubbery; while in its Colonial hall, unoccupied, still hangs the family coat of arms.

There were many separate settlements early, each with its saw-mill, tavern, and blacksmith shop. Some settlements added a cider-mill. At North Hartland, there was a place where hand-made cloth was heckled with teasels, and there were two rope-walks, just why, the author does not know; but, as two sea-captains lived in town after the War of 1812 — Capt. James O’Hara and Capt. John Hammond, their influence may explain the matter.

From 1778 until about 1870, with some interruptions the June training of Hartland’s militia-men was an established feature of the town’s life, and the military reports of men equipped for service, previous to the War of 1812 are very numerous. The earliest report in the town records is dated 1808. The Webster family has the original documents of Capt. John Webster and of many other Captains but the author has never seen one of Capt. David Sumner’s Company — the one that served at Plattsburg. A surprising number of Hartland men prepared for the War of 1812.

A “Resolution” entered in one of the town books by Daniel Breck, town clerk, declares, “That we will never submit to foreign or domestic outrage. That we will do our utmost to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections,

& repel invasions, and to this end ‘praying the God of armies to make bare his arm’ we pledge our lives and Fortunes & our sacred honor.”

All the old flint-locks were brought out and they were many.

Only a few of those who actually went to war have been determined. Among them were: Messrs. Perkins Bagley, Thomas Bagley, Joseph Burk, Daniel Childs, Eldad French, Jonathan Hodgman, William Livermore, Joseph Livermore, Isaac Morgan, Sr., Isaac Morgan, Jr., and Dr. Friend Sturtevant.

A brief item accounts for three men thus:

Capt. Webster : We have enlisted 3 men out of your Company Hial Paul, Otis fish, Perez W. Gallup witch I return their names to you.

Lieut. Dodge.

State of VT. To Hiel Paul Secy.

Greeting.

You are hereby ordered in the name and by the authority of the State of Vt. immediately to warn those persons whose names are hereunto annexed to meet on the company parade at Hartland meeting House on thursday the 2nd day of February next at 12 O’clock for the purpose of raising our proportion of one hundred thousand men according to an act of Congress and there wait for further orders, thereof fail not but a due return make of your doing thereon according to Law. Dated at Hartland this 23rd day of January 1809.

Consider Alexander, Captain.

Serj. Benjamin Campbell

Do Hiel Paul

Capt. Seth Tin(k?)um

Oren Liscomb

Amos Ashley

Dan Marsh

John Stevens

Zenas Webster

Seth Wood Jr.

Benjamin Barron Jr.

Gideon G. Goodspeare

Theron Rust

Wm. Nutting

Jesse Billings

Moses Billings

Jonas Benjamin |

Orea Rawson

David Badger

Abjah Benjamin

Elijah Green

Samuel Healey Jr.

Elida Sabin

William Sabin

Roswell Hill

James H. Durrer

Thomas Perkins

George Marsh

Timothy Moore

James Nutting

John Billings

Jesse Benjamin

Otes Marsh |

From the above it is apparent that definite preparations for a second war with Britain were being made in Hartland three years before the breaking out of hostilities. However, only a very few items on these preparations are recorded in the town books; but, of them, the following entered in the report of the town meeting of March 5, 1812 is of sime interest: the Freemen were asked to “act on … the article.

5th To build a Magazine for storing the towns stock of powder & lead and also to build a house for storing the Cannon and apparatus belonging to Capt. Dodge’s company.

In reviewing the accessible military returns of officers and men prepared by Hartland for the War of 1812, the author finds more than two hundred reported in the town records as equipped for service, apart from certain of those listed in Capt. John Webster papers. The Webster lists show about two hundred trained by Capt. Webster alone; but only a small part of these were fully equipped. If those partly equipped in other companies could be known, the list for the town would be very long; and, as it is, the names given represent nearly every Hartland family of early times.

The equipment required in Capt. Webster’s company was guns, cartridge boxes, bayonets, bayonet belts, priming wires, brushes, and flints.

The captains thuse far determined were: Capts. Consider Alenander, Andrew Dodge, Abel Farwell, Caleb Hendrick, Seth Limum (Lyman?), Levi Lull, Humphrey Rood Jr., David Sumner, and John Webster. Judge Luce once said of his neighbor, “If all men were like Caleb Hendrick (the Capt. of Artillery), there would be no use for poor-houses, jails, court houses, or prisons.” [A quotation from B. P. Ruggles’ “Hartland Sayings.”]

The liutenants were: Infantry– 1st Liuts. William Barrett, Charles Livermore, John Webster; 2d Liut. Simon P. Hoffman. Cavalry– 1st Liuts. Samuel Perkins, jr., Humphrey Rood, Daniel Smith; 2d Liut. Andrew Dodge. Artilery– Liuts. Andres Dodge, Simon P. Hoffman; Ishmael Tewksbury.

The sergeants were: Sergs. Daniel Ashley, Marston Cabot, Jr., Benj. Campbell, Ezra Child, Cyrus Cushman, John R. Densmore, Sam’l A. Fielding, Sam’l Healey, Jr., Simon P. Hoffman, George Latimer, Levi Lull, Dan’l Marsh, Hial Paul, Sullivan Rust, Frederick Sillsbury, Adin Spaulding, Alvan Taylor, Ishmael Tewksbury, John O. Willard, John V. Williams.

The corporals were: Corps. John Barrel, William Benton, Joseph Bryant, Jonathan Burk, George Cabot, Hugh Campbell, Lot C. Hodgman, Alexander Holton, George Latimer, Sullivan Marcy, Dan’l Marsh, George Miller, Amasa Richardson, Ruggles Spooner, Edward Swan, Alvan Taylor, Thomas Weeden.

The musicians were: Drummers — Joseph Amsden, Jacob Gillman, Adin Spaulding, Alvan Taylor, Spensor Tracey, John O. Willard,; Fifers — Elad Alexander, Elijah Alexander, William Dean, Elisha Rust; Cornetists — Humphrey Rood, Moses Tewksbury; Undefined — Josiah Glading, Noah Shepard.

Two minors are recorded as training in the Hartland militia — Joseph Dunbar and Frederick S. Gallup. Otis Fish, who was enlisted from Capt. Webster’s company, was one of the members of the “1st Company of Matross (?)” recorded June 23, 1813.

The companies trained in every section of Hartland, and they trained so often that the men and boys became thoroughly acquainted with each other and with the topography of their town &ndash. an attainment which would in itself justify universal military drill today. Among the places mentioned as parade grounds, in the military orders of Capt. Consider Alexander and Capt. John Webster, were those at Capt. Oliver Stevens’, Simon P. Hoffman’s, Samuel Taylor’s, Laban Webster’s and “Hartland Meeting House.”

Mrs. H. H. Miller has a scarlet coat and cap which were owned by the Weed family, used in the drills of the Hartland militia, and which are probably typical in style. Capt. Andrew Dodge’s scarlet coat is another of Hartland’s valued relics.

In the Albert Powers pasture, near the Woodstock line, is a large quartz rock by which a Hartland militia company is said to have camped while on its way to Plattsburgh during the War of 1812. This was the men’s first camp on their way out and was called, “The White Rock Camp.”

On Sept. 19, 1809, there was a Regimental Review of arms and exercise at Simon P. Hoffman’s.

Included in the First or “Hartland Regiment” were companies representing Hartland, Windsor, Hartford, and Norwich; and, in the autumn of 1814, these mustered at Woodstock for the famous review of the “1st Brigade, 4th Division of the Militia of Vermont.” Col. Consider Alexander was the commander of the First Regiment. A Hartland company of artillery and a Hartland squadron of cavalry, Humphrey Rood commander, were attached, with others, to the brigade.

Besides the men already named as serving in the War of 1812 from Hartland were: Daniel Bagley, Parker Bagley, Alfred Barrell, Phineas Barrell, Rufus Marcy, and Willard Marcy, Jr.

Mr. Leeuel Spooner, though not a Hartland soldier, was the last survivor of America’s last war with Britain whom the author remembers. He spoke at Woodstock one Fourth of July, and being very aged, he seemed like a battered oak of the forest as he rose in the audience; but he was sound at heart and he voiced a patriot’s soul, while everybody present applauded him roundly.

Mr. Perkins Bagley was Hartland’s last survivor of the War of American Seamen, and Isaac Morgan, Jr., who enlisted at the age of fourteen, was the next to the last. Mr. Mogan used to tell many anecdotes of battles in which local men engaged; but the author remembers only the orders at the battle of Niagara which were “Rush! Rush!” One of his neighbors remembers how, when he became excited in an argument, he would exclaim, “You know nothing about fighting! You know nothing about fighting! The Falls of Nigary and the Battle of Chippewa!” Sometimes he would say, “You know nothing about fighting! Ground arms!”

In looking through the Hartland records of events that occurred immediately before and soon after the War of 1812, one is surprised to find many “Warnings to Depart” issued against perfectly respectable heads of families who came to settle in town, to prevent their gaining a residence. The injustice of the law requiring such warnings was perceived by Vermonters after a time and the statute was repealed.

Some curious entries are those on the marks which were used by stock-raisers in distinguishing their cattle and sheep as:

David H. Sumner’s mark for cattle and sheep is a smooth Crop off the left Ear & a half penny under the right ear.

– Recorded June 6, 1814, by E. Spooner, Town Clerk.

John W. Cary’s Mark for Sheep is a swallow-tail in left ear & a half crop the under side of the right ear.

– Recorded January 18, 1823 by D. Ashley, Town Clerk.

Agricultural development followed the war, and Hartland became celebrated for its farming — for its live-stock, wool, and maple sugar.

For example, we read from an old letter: “Esq. Denison, as everybody called him, represented his town in the legislature — he was generally school committee in my early days and held various offices in town — his farm was one of the best cultivated in Windsor, Co. He kept a large dairy of the finest grades and hundreds of merino sheep roamed over his fertile pastures.”

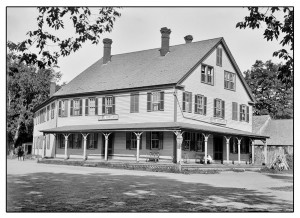

Col. Denison, a soldier of the Revolution, settled very early on the place now owned by the descendants of Mr. Truman Slayton. He built first a log house, and its hearthstone and chimney still remain; then he built, in 1794, the present large farmhouse with its beautiful verandas. Here is a picture of Squire Denison and his wife: “He was very careful to give all his children a good education; Geo. W. was a prominent lawyer in St. Louis, Missouri. He was always very kind to the sick, would visit those in the neighborhood who were ill and see that they had proper care, would furnish watchers, and when they were convalescing would carry them dainties to tempt their appetites — would often dress a spring lamb or chicken or anything he thought would be strenghening to the patient. His good wife had the same kindly nature; not only would she carry the sick and poor dainties from her own table but would do sewing for them gratis. She was a very fine singer, would always sing in church and at funerals.”

In another letter occurs this description: “Ward Cotton was a well-to-do farmer, owning several good farms at the ‘middle of town.’ He always kept a fine herd of cows, but his money-making industry was raising for wool — keeping several hundred sheep — having a shepherd to watch and care for them as they roamed the green pastures. During the Civil War he sold his wool for a dollar a pound. He raised flax and to a certain extent manufactured his own cloth for family use. Mr. Cotton made a large amount of maple sugar, some years two thousand pounds or more. He used the old fashion wooden buckets for holding sap, and boiled it down in iron pans, in a large sugar house.”

In the early part of the nineteenth century Hartland led the county in the quality of its agricultural products, and often in modern times it has taken first prizes on “town teams” of oxen. The raising of sheep and cattle for market was an important industry here during the last century, and Squire Asa Weed was one of the prosperous farmers who sent “a drove” to Boston once or twice a year at least. His son Nathaniel continued the business and his grandson Nathaniel did the same.

“Blind French” was a successful drover who was generally known and liked.

On Jan. 11, 1845, Mr. Leonard H. Hamilton of New York City wrote to Luther Damon, Esq.: “I was very glad to hear so good account of my stock. I do not care how much they eat so they do not waste. Money is now worth in the street 9 to 12 per cent per annum. The Banks charge 6 per cent fo 60 day paper and over that time 7 pr. ct.”

Consequent upon the production of many cattle, sheep, etc., was the building of tanneries. Mr. Levi Marcy had a tannery early at Fieldsville; but he had a farm likewise, and, in common with nearly all the other heads of families, he went once or twice a winter to Boston with goods. He carried tanned leather, cheese, dried apple, beans, grains, dressed hogs, etc., bringing back West India goods, quintals of fish (cod, mackerel, salmon, herring) kegs of oysters, boxes of raisins, webs of cotton cloth, prints, etc., and a bladder of snuff for his aged mother. He used a “double sleigh,” Miss Helen Marcy, his granddaughter said, when he started from Hartland. He went to Windsor, Claremont, Newport, paying tolls often, crossed Sunapee Lake on the ice to New London, then drove to Nashua where he put up his span of horses. At Nashua, after trains were in use, he loaded his produce upon a car and went on to Boston by rail.

No one seems to know where the Joel Shurtleff tannery was, it was “so far back.” Mr. Joseph Morgan, son of James Morgan, the farmer, and grandson of Isaac Morgan, Sr., the pioneer, had one of the best farms for stock in West Hartland and the largest apple orchard in town. This farm and orchard have improved with time, and ar now owned by Mr. J. S. Darling. Mr. Morgan and his neighbors of the Elisha Gallup family produced excellent honey. The ladies of these two households were famous for their poultry, butter, and cheese, their fine needlework and paintings and for their old fashioned gardens containing herbs. Mr. Luther Damon had a beautiful farm on the opposite side of the town near Windsor. He mad many trips to Boston with produce, and the garden kept by Mrs. Damon and her descendants is one of the loveliest of its kind. The E. M. Goodwin and Henry Britton farms near by ar among the best of the meadow farms. The E. S. Ainsworth farm at “The Centre,” called “Cornbill” has on it one of the oldest local landmarks — the broken headstones of the graves of pioneers. The “Old Asa Taylor Farm” in North Hartland, now owned by Mr. Walter Wood, is on of the many in that section considered superior. Its farmhouse is of the oldest. The Dunbar farms, formerly the Gallup farms, are unsurpassed as corn lands; while the Daniels or Henry Dunbar farm is one of the best on the Connecticut River. On the Lamb farm was the “Hammond and Lamb Distillery.” The firm made cider brandy, rye whiskey, and other liquors, and the copper still is yet in the possession of the Lamb family. The author remembers hearing Mr. Daniel F. Morgan tell of the excellent potato whisky that used to be distilled on the Mackenzie farm in the Densmore District.

Broom corn was raised extensively by the farmers at one time, especially when the Healey family manufactured brooms and brushes. At the Dr. Harding place, silk culture was carried on, and a few of the mulberry trees survived until quite recently.

Shoemakers, tailors, tailoresses, and dressmakers long went from house to house plying their trade for their board and a few shillings a week. Certain erratic and simple persons have always lodged at will among the townspeople. Tin-peddlers have been an established feature of Hartland life, and to this day they perform an acceptable work in bartering their goods, for odds and ends. Everyone remembers “Tinker” Morrison, who mended clocks and tinware. He was a college educated man, silent and dignified, with a tall lank frame and a swarthy complexion. He had a family of excellent children. There have been several tin shops; also harness shops and shoe shops.

At both the Three Corners and the Four Corners was “The Harding Marble Shop” at different times. At Martinsville a man by the name of Zebina Spaulding made guns in a shop opposite “Martin’s Mill” on Lull Brook — shot guns and other fowling pieces. He was fatally shot by the accidental discharge of an old Windsor revolver. William Henry Lemmex, born in 1805, and “a gentleman of the old school,” as his biographer styled him, conducted a store and a mill in Hartland for fifteen years, beginning with 1829. The mill, called “The Lemmex Woolen Mill” stood by the Mill Gorge and near the site of the carding mill. Before the foundry building was used by Mr. Francis Gilbert, it had served as a woolen mill for the Sturtevant brothers when they began milling here, and around 1850 it was used by Frederick Sillsbury as a clothes pin factory. William Colston and James Petrie, British soldiers who settled in Hartland, were weavers. The former lived on the Charles O’Neill farm; the latter on the Albourne Lull farm. The “Petrie and Sturtevant Woolen Mill” was by the Mill Gorge.

For many years there was on Lull Brook a large “shop” built by Mr. Frederick English, the mechanical genius. Mr. Benjamin Livermore, the relative of Mr. English’s, invented “Livermore’s Permutation Typograph or Pocket Printing Machine” in 1857. It was described thus by The Boston Daily Traveler: “The polished steel case, which contains the apparatus, is five inches long, and two and a half inches broad, and one and a half inches thick. This contains the type, the ink, the paper, and the machinery. At one end of the case are six keys, on which the fingers of the operator play, as on a piano. The rapidity of the printing is about equal to that of writing with a pen, as most persons write. One would not believe all this possible beforehand, but when he is presented with a sentence legibly printed and undeniably printed then and there, he is no longer skeptical.” Several college professors wrote a good word for it, and William Lloyd Garrison closed his commendation with the words, “Success to whatever shall lessen toil and facilitate the action of the mind.”

Mr. Livermore invented also a cement pipe for conveying spring water, and it was manufactured on the old Joseph Dunbar or T. A. Kneen farm by Mr. Norman Dunbar. However, it proved of little value, as freezing cracked it. Sections of it, which are three or four inches in diameter may be seen at “Sky Farm,” used in borders for flower-beds.

Mr. A. J. Stevens says that, at the Four Corners, there was a saw mill, a hotel, and a store before there were any public buildings at the Tree Corners. Thomas Cobb’s saw-mill, on the brook west of the L. A. Shedd place, had a sash and blind shop connected with it at one time. Azro Burgett, the Hessian, was a wheelwright who had a shop near the Four Corners, and Mr. Gustavus Morey’s father had a similar shop. Mr. O. F. Hemenway had a carriage shop on one of the old Morey places, near the B. F. Hatch place, and west of the Four Corners two miles or so.

At present the oldest house in the village is thought to be that owned and occupied by Mr. and Mrs. J. A. Rich, formerly the home of the Rice sisters. It was originally a tavern and afterwards used for a store. The brick school house of today was the Stocker store, and it contained the town clerk’s office when Eben M. Stocker was town clerk. In recent years there has been added to the village a milk station and factory for either butter or cheese. It stands just west of the “Hayes House,” on the same side of the road and near the bridge. The building now used as a town hall was put up by Mr. Wesley Labaree who kept a store on the present Marcy store site and who built the watering trough near the Judge Luce place. It was made, some say, from the old dance hall that formed a part of the brick hotel that once stood on the corner near the town hall — one of the principal buildings at the Four Corners in 1822. For a while the town hall building was used as a clothes-pin factory. Two years it was used as a Lodge room for Hartland Masons. March 7, 1865 the town voted — “that the Selectmen procure a place for the Militia Company to drill in and keep Equipment in.” The hall built by Mr. Labaree was secured. The “Equipment” was stored there, and, in wet weather, the “Boys in Blue” drilled there. This year the Ladies’ Aid of the “West Parish” has bought a piano for the hall and has papered the upper room and pit it in order.

About a mile west of Hartland Four Corners, on the hill road to Woodstock, is the “Town Farm,” which was purchased of Mr. Jacob Tewksbury in the earl seventies of the last century by A. B. Burk, the town clerk, and Asa Weed, the selectman. Mr. Burk said, when he was making the purchase, “I want as good a farm as there is in town and I want it near the village.” The farm had previously been the home of Marston Cabot, the surveyor, — a brother of Francis Cabot, the large landholder. It had on it a spring of delicious water known as “The Cabot Spring.” The “Old Town Farm” was near Barron Hill, where the ancestors of the White Mountain “Hotel Kings” named Barron lived, and it was in the neighborhood of the farms of the pioneers—Solomon Brown and Timothy Grow. The original Solomon Brown farm is now the Jerome H. Eastman farm.

The town house was voted to be built in 1790 as a “work-house erected or procured in said Town for the reception correction (of) Idle mismanaging persons in sd Town,” and Samuel Williams, William Gallup, and Joseph Grow were elected a committee “to erect or provide said House.” A tax was voted “of one penny on the pound for the year 1790 to be paid into the Treasury by the 25th of December next in wheat at 12c per quart or other grain.”

After the house was burned, Mr. Oliver Brothers, as agent, sold the farm to Mr. Henry Dunbar, and it is now the property of his son, Mr. Teague Dunbar. The region of this farm is most picturesque and a favorite picnic ground for North Hartland people.

The Adventists built in 1902, under the influence largely of George WIlliams family, a little church on Barron Hill, and there services have been held much of the time since. The “Densmore Neighborhood” years ago was almost an Adventist settlement, and two ministers of that faith—Revs. Wells Hadley and Henry Holt, went from there.

About fifty years ago, there were many Spiritualists who took the waters at the “Spring House” in Fieldsville, and sometimes religious services would be held there attended by as many as two hundred Spiritualists. Now there are no such meetings in town.

In 1830, the Episcopal church at North Hartland was removed from its site on the George P. Eastman place to the present one, since which time it has been a true “Union Church.”

The Congregational church, built in 1834, and the Methodist church, built in 1839, are at Hartland Village. They have been remodeled and beautifully finished inside, and they are both doing good Christian work. East of the Congregational church is a beautiful cemetery.

Union services were held the day following the Anniversary Celebration, at the Universalist church at Hartland Four Corners, which Mrs. H. H. Miller describes thus: “An invitation was extended to the other Churches to unite in this ‘Old Home Service.’ They accepted, and the outcome was one of the finest services ever held in the church. Revs. Hill and Parker, from the other Churches, Mr. and Mrs. Barney assisting in the service. The sermon was given by Ref. Stanley G. Spear and was very interesting, being of a reminiscent nature. There was a splendid choir with all the singers from the other Churches, Mrs. Alice (Sturtevant) Wills at the organ. Solos were rendered by Misses Minnie Barbour, and Florence M. Sturtevant of Hartford, Conn., while the Centennial Hymn composed by Mr. Sturtevant for our Church Centennial was used. The congregation was very large.”

In 1828, Sumner’s Village or the Three Corners was laid out by the selectman — Stephen Paine, Asa Weed, and Alvin Taylor, according to the “Village Law,” and became Hartland Village. Of this place Mr. W. R. Sturtevant spoke thus in his historical address given at the Anniversary Celebration: “The first store was built near the site of the old Pound on the Quechee road and was kept by Johnny R. Gibson, and Jacob Dimick, late a highly respected citizen of Hartford, Vt., who kept a store in Quechee VIllage, was his clerk. The first schoolhouse was built here and the second at Hartland Village half way up the hill on the place lately occupied by B. F. Labaree. It was of brick and was heated by a fireplace, in one end of which was kept a bunch of withes, with which the master used to chastize unruly boys. They were kept there for the purpose of keeping them dry so when they were used they would cut more smartly than if green. The hotel, the old Congregational Parsonage House are (among) the oldest houses in this vicinity. The hotel was built by Isaac Stevens, grandfather of the present generation at Hartland. He was a soldier of the Revolution, enlisted Nov., 26, 1775. He owned a large portion of the land in this vicinity. The hotel was occupied certainly as early as 1804, for my grandfather stopped there then on his way to Woodstock from Pittsfield, Mass. My grandmother told me at that time the country west of the hotel was covered with a heavy growth of pine timber. The road to Hartland 4 Corners led out of the village by the Quechee road and veered west near the site of the old Pound and came into the present road near the large elm tree opposite the Barbour place. This elm tree stands on the corner of one of the 100 acre lots as originally laid out. It is related that the late Daniel Ashley, when a boy, while at work in a field near by, hung his jacked in the fork of this tre whidch is now 40 feet or more from the ground.”

Daniel Ashley afterwards owned the present Guy Graham place and had extensive brickworks there.

Mr. F. C. Sturtevant, in his Anniversary address on “Quaint Characters of Hartland” said of the old hotel, “I remember when the stage, with from four to six horses, would come thundering into town with a toot of the horn and a crack of the whiplash and pull up to the Merritt’s Pavilion (Lewis Merritt’s), change horses, all passengers go into the bar-room and get a good drink of Santa Cruz rum and then continue the journey.”

The “Old Road” at Hartland Village followed along by Lull Brook in very early times, Mr. A. J. Stevens says, instead of turning across the bridge at the head of Mill Gorge. This was probably before the Stevens hotel was build and in the days of Lull Tavern.

Mr. Pliny Smith, whose family were notoriously fine singers, drove the stage from Hartland to South Woodstock by way of the “Burk Tavern Stand” for many years.

Mr. W. H. Gilds now comes into the village as the Hartland “Rural Free Delivery Carrier.” Mrs. Giles is a descendant of Noah Aldrich, who settled on the Almond Davis farm. Noah Aldrich, who died in 1818, aged 81, was a patriot of the Revolution and his grave is in the cemetery on the plain.

Mr. Albert A. Sturtevant has told his family of the games that the village boys used to play: “Two-Old Cat,” “H’I Spy,” “Touch-the-goal,” and “Wicket Fall.” The last was a game played on the south side of the common before the Richardson house. In wicket ball, the boys laid a plank across the common supported by a brick at each end; then they used bats with which to strike a ball back, and forth. The bat was round, long, and flattened out at the end. Some of the boys used to go up on the Larabee Cliffs to sing and roast corn in the fall, and there used to be occasional wrestling matches on the “Green” in front of the W. R. Sturtevant’s store.

Mr. Sturtevant says that Lovejoy and Taylor built a store about 1804 near the site of his present one and that he has two signs, one, “Sumner and Sturtevant,” the other, “Phelps and Barker, 1830”; also that Mr. Leonard Hamilton built the “Sturtevant Store” about 1840, and that in 1851, Mr. Paul D. Richardson built the store leased by Mr. L. I. Walker now. In the latter Mr. Benjamin F. Labaree served the public as a highly respected merchant many years. Mr. Sturtevant says further that the only store ever built in Hartland by the Hon. David H. Sumner was burned soon after the opening of the Civil War, or about fifty years ago. It stood below the site of the present freight depot.

The Alden or “Old Reuben Weld” house at Hartland Village was moved up from “The Plain&rdquo about 1814. Capt. James Campbell was the master workman and Eliakim Spooner, Esq., the lawyer, was the proprietor of the house then. Reuben Weld lived there around 1820. Beyond this Alden house, stood the one recently moved west of the Edgerton or Barbour place and now occupied by Mr. William Lamphear. It was built by Lawyer Merrill, Mr. W. R. Sturtevant says, and, after a few years, was used as a private school for young people of both sexes. About the middle of the last century, Miss Krams, later Mrs. Wm. H. Sabin, of Windsor, taught a school for girls at the Three Corners; and, in the sixties, Miss Mary Hyde had a private fitting-school for young men and young women, and Miss Leonora Robinson, now Mrs. W. R. Sturtevant, was her assistant. A fitting-school for college was kept earlier by Isaac N. Cushman, who became a lawyer of marked ability and who lived in the brick house on the hill approached by many steps. The school was on the site of the Pound, and Mr. John Webster had an uncle who fitted for college there.

Hartland Village is so attractively located and so rich in historical association that it draws may city visitors every summer.

The story of North Hartland as a thriving modern village is almost exclusively that of the woolen mill built by Mr. Oliver Brothers. The place has grown constantly in attractiveness during recent years. It has many pleasant homes, a good general store conducted by Mr. W. D. Spaulding, a flourishing woolen mill, the historic church, a Grange hall, the best school building in Hartland, a beautiful park, shaded streets, and the two rivers with their rich meadows and picturesque falls.

The history of Sumner’s Falls as a settlement is entirely of the past, scarcely a vestige remains of its once busy life. This history has been given in the Windsor County Gazetter, however; so only less accessible items will be mentioned here. A son of one of the early settlers above the plain writes thus of old times:

“After Timothy Lull settled on Lull Brook, Gideon Woodward came up the Connecticut River with such tools as he could draw on a hand sled. He concluded to settle on the east side of the river. Peter Gilson soon moved up and settled on the plain. Joseph Livermore lived on the plain and raised a family of twelve children. Harry Emerson settled north of the plain near Sumner’s Falls. Jo Call moved up on the plain. He was one of the great wrestlers of his day. A man walked up from Massachusetts to wrestle with him, but Jo was not at home, and his sister told the man he would not be at home for three or four days. He said he was sorry, for he was in a hurry to get back. She told him to step out into the yard and if he could throw her he could stay and wrestle with Jo; but he didn’t have to stay long. She laid him on his back short meter.

“Ezra Sleeper settled north of Sumner’s Falls. ‘Johnny’ Warner lived on the place with him and kept school in his house. After school hours, he and the scholars set out maples on the east side of the road. They stand there today and are about 115 years old. Perez Gallup was next. He owned about 640 acres. He built the Gallup burying ground on the west side of the road about one mile south of North Hartland — a very peculiar man. He hewed out a stone to lay over his coffin which took four oxen to haul to the burying ground.

“The church was built by the inhabitants of North Hartland. Thomas Shaw hewed most of the timbers. Samuel Taylor worked, Merrill Kilburn, the Russes. The oldest house in North Hartland is what is called the Rawson place, now owned by Daniel Willard.

“The church was built by the inhabitants of North Hartland. Thomas Shaw hewed most of the timbers. Samuel Taylor worked, Merrill Kilburn, the Russes. The oldest house in North Hartland is what is called the Rawson place, now owned by Daniel Willard.

The Lawtons and Spooners settled here at an early date back on the Hill. They were afraid of the frosts. The Willards and Millers lived at North Hartland later. George Miller owned the ferry at North Hartland. In 1848 they were at work on the Vermont Central Railroad which was very exciting to all the farmers along the line.“ (The author has changed the forms in this letter somewhat.)

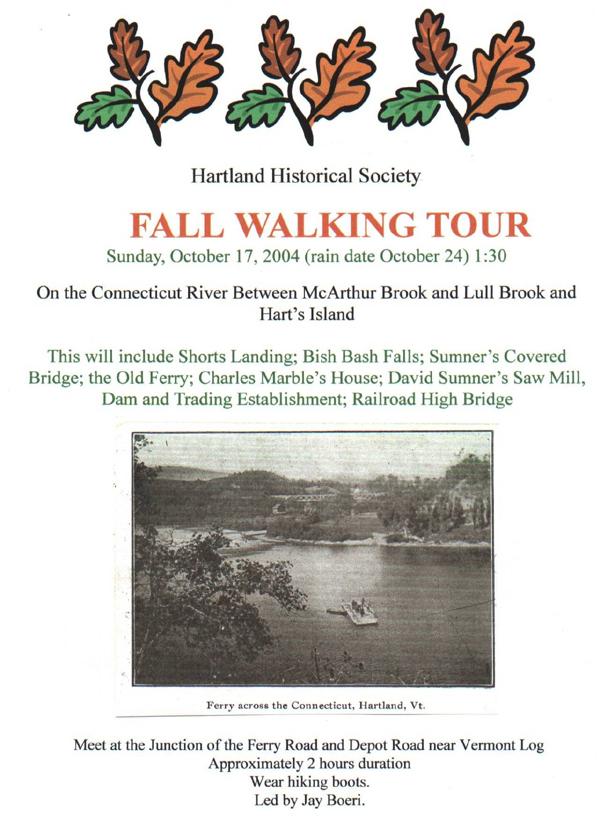

October 23 1794, Perez Gallup received from the Legislature a grant of “the exclusive privilege of locking and continuing locks on Water Quechee falls on Connecticut River through his own land in Hartland,” as W. H. Tucker, the historian, expressed it. The toll for loaded boats was authorized to be 18c per ton, the same for each 1000 feet of boards and timber, and for each 6000 feet of shingles.

The property of “The Company for Rendering Connecticut River Navigable by Water Quechee Falls” passed into the hands of David H. Sumner, Esq., Oct. 9, 1809, including the saw mill and the use of the falls. Then, following the charter given Nov., 5, 1830, to “The Connecticut River Valley Steamboat Company” sprang up the canal and locks at Sumner’s Falls and the roads to that place. In 1834, the “Aterquechey Canal” was one of the three canals in Vermont—the “Aterquechey,” “Bellows Falls,” and ”White River“ canals.

A bridge had been built in 1821. Mr. Sumner, who owned the whole town of Dalton, N. H., passed immense quantities of lumber from that place and from others in northern Vermont and New Hampshire down the river to Hartford, receiving in return West India goods, salt, iron, etc., loaded upon flat boats until the steamboats came into use.

The steamers, however, were not successful, and finally only boats were plied between locks. Dalton and Sumner’s Falls were the manufacturing centres for the lumber of the Connecticut River trade.

The articles other than lumber that composed the outgoing cargoes were similar to those taken to Boston by team. After 1836, the roads to Boston were so good that river traffic began to lessen. Freshets swept away the two bridges built across the river; finally, in 1848, the railroad with its substantial iron bridge over Lull Brook was built and the old ways of traffic passed out of existence. Yet, every spring, even now, one sees “drives” of logs, guided by red-frocked lumbermen from the north, plunging over the rocks at Sumner’s Falls on their way to Massachusetts or Connecticut towns as in former days.