Installment 3

Camp Life in Virginia for the “Nine Months Men”

The last HHS newsletter described the formation of the 2nd Vermont Infantry Brigade in response to President Lincoln’s call for 300,000 more volunteers. About four dozen Hartland men responded by joining the 12th or 16th infantry regiments as “Nine Months Men.” By the fall of 1862 these men were in camps in Virginia. I mentioned Camp Vermont as a main camp and while the five regiments of the 2nd Vermont Brigade were all in the same general area south and west of Washington, they occupied several camps along the outer defense line of Washington.

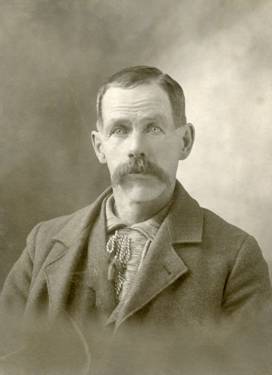

This article will describe in more detail what life in the camps was like for the men who spent most of their service there. This is possible because HHS has a collection of 60 rather lengthy letters written by Pvt. James H. Bowers to his wife Maroa. Pvt. Bowers was 23 when he enlisted from West Windsor and was assigned to Co. A, 12th Vermont Infantry Regiment. James was in the army from 10/4/1862 to 7/14/1863. Several Hartland men were in that 101-soldier company, including William Allen, Oscar Davis, Reuben Lamphear, James Nash, James Rogers, George Spear, and Clinton Willard.

Family records show he and Maroa had been married a year and a half when he enlisted. They had their first child in 1864 and a son, Albert, was born in 1869. Maroa died young, and James married twice more. He died in 1909. Albert moved to Hartland and Albert’s son Jimmy, grandson Eric, and great grandson Scott all live near the Bowers farm, now known as the Flower Farm.

The letters were organized and typed by James’s granddaughter, Rena Jenne Houghton in 1968.

Les Motschman

James Henry Bowers

-1-

October 11th, 1862 (The first letter from Washington includes a pencil sketch of the Capitol Building at the top of the page, below James writes I have been in the United States Capitol.

[Describing the journey from Camp Lincoln in Brattleboro to Washington]:

Marched 3 miles to where we took the cars. Tuesday at 9 o’clock [p.m.] arrived in New Haven at daylight, took a steamboat to New Jersey, then took the cars through Trenton, the capital of New Jersey. Took supper at 8 o’clock in Philadelphia, arrived in Baltimore at 6 o’clock [a.m.] got breakfast at 10 o’clock, took the cars for Washington at 2 o’clock and arrived there 9 o’clock [p.m.] Thursday. The boys stood the journey first rate. If I live to come home, I will tell you all about it. Have you received my bounty?

October 23rd , 1862 (Camp Casey, Capitol Hill)

I am well this morning. O, how I wish I could step in and take breakfast with you. It is quite cold, we have warm days and cold nights. Horrace Houghton died yesterday. Shedd is here, he is going to have his body embalmed, and carry it home.

October 29th, 1862 (Camp Casey, Capitol Hill)

Mr. Hopkins from Windsor died of a fever. The Captain is some better, his wife is here taken care of him.

The nine months men are all here now. It is rumored we might spend the winter in Washington.

Our wagoner, Mr. Brown, got drunk the other day and whipped one of his mules so bad they had to kill him. Brown is in the guard house now.

October 31st, 1862 (Camp Seward, Virginia)

You will see we are in the rebels’ country now. The whole Vermont Brigade marched through the city and over the long bridge into Virginia. I tell you, it was a splendid sight to see those five thousand soldiers all in a mile and a half string. We marched in four ranks with our regiment in the lead.

The land here is very pleasant with good water. It once belonged to the rebel General Lee.

November 3rd, 1862 (Camp near Alexandria, Virginia)

We have moved again. I have not seen a rebel yet except for prisoners. I do not like it here very much. The inhabitants are mostly Negroes. Butter is 36 cents a pound, cheese 20 and apples 3 for 5 cents-so I cannot eat a great deal of such stuff or my money would not hold out. If we are stationed here this winter, you should send me some things. I know it will cost considerable, but I cannot help that. I do not feel I should deprive myself of everything for the sake of making money.

November 18th, 1862 (Camp Vermont, Virginia)

I received a letter from you last night and you had better believe I was glad to hear you was well. My health is first rate. We are busy building our barracks so we can spend the winter here.

First we dig a trench 20 inches deep and a foot wide, then we put split 8-foot white oak logs on end in the ditch and fill around them with dirt to make the walls. When the canvas roof is up, it will look like a house. We are going to plaster the cracks with Virginia mud and if it sticks as well as it does to our boots, it should keep the wind out. I think we can make ourselves very comfortable.

November 26, 1862 (Camp Vermont, Virginia) [Leading up to Thanksgiving Day]

I was glad to hear from you and that you are well. My health is very good. I was glad for the two dollars you sent me for I was entirely out of money. I think we should be thankful that we can hear from one another so often.

Martin had a box of stuff come Monday from Hartland, and then he had some more come tonight in Hammond’s box. I ate the best breakfast of my life this morning. I tell you, Martin is a swell fellow.

I have not the fear that I expected I would. I have been on picket duty twice and have not seen rebels.

-2-

November 30, 1862 (Camp Vermont, Virginia)

We are very busy here nowadays. The 13th, 14th and 15th regiments have left here, leaving only the 16th besides our 12th to do picket duties. We are sometimes sent out four or five miles from camp. There are two or three men stationed at a post. We stay at a post for 8 hours. When relieved we put our rubber blanket on the ground and our woolen blankets over us and sleep just like a pig.

December 7th, 1862 (Camp Vermont, Virginia)

We bought a little box stove for our house. It has an oven so we can bake potatoes or warm up chicken pies or turkey and fixings.

One man from our company is going home. Mr. Lamphere from Hartland died this morning of brain fever.

The boys had whiskey dealt out to them yesterday, but I did not drink any.

December 13th, 1862 (Camp near Fairfax Court House, Virginia)

You will see that the whole brigade has moved from Camp Vermont. It came pretty tough for us to leave our barracks we had just fixed up for winter. The army is moving forward and we have to move up to take the place of those who have gone forward.

I learnt this morning that General Burnside has burnt Fredericksburg and is marching on Richmond.

January 3rd, 1863 (Camp Fairfax, Virginia)

A very pleasant day here today. I done my washing this forenoon. A lot of us went down to the brook and built a fire and het up some water for washing. I do not believe in washing Saturday, but we have to wash when we have the chance.

We have our tent stockaded so it’s as comfortable as our barracks at Camp Vermont.

You say you have 6 sheep. I think the sheep and calf would eat what hay I got up.

January 9th, 1863 (Camp Fairfax, Virginia)

We shall have all the fighting we want, but that is what we came for. If I ever go into battle, I hope I shall be able to do my duty and if I fall, I hope to die in a good cause, but I fear the disease in camp more than I do the enemy’s balls.

You should send me some letter stamps if you can get them. What have you done with the hog money?

January 12th, 1863 (Camp Fairfax, Virginia) [after receiving butter]

I tell you, Maroa, that is the best butter I ever eat in my life. I make a cup of tea and then put in a piece of butter and crumble in my hard crackers and it goes first rate.

I get your letters the third day after they are mailed. We get the Journal [Windsor paper?] every Monday night. That is quicker than we used to get it at home sometimes.

We have plenty of company now days. What’s left of a brigade of PA. Buck Tails came in here the other night. It is interesting to hear them tell what they been through. They have seen hard service, I think 13 battles. The last they was in was Fredericksburg where they were cut up pretty bad. They were in the 7 Days fight before Richmond, also Antietam, and South Mountain, and Bull Run. They have lost their knapsacks and blankets four times and had to pay for new ones. They are smart as steel but have been out so long they are pretty rough.

January 18th, 1863 (Camp Fairfax, Virginia)

A letter from Martin (Herrick):

I write you at the request of your husband as he and Charley [James’s brother] are sicke with the measles. I think they are doing as well as can be expected. I will sit with them tonight. I don’t want you to worry, they have good care.

January 19th – The boys rested very well. I think they will soon get up again.

Martin

-3-

The regiment moved ten miles to Wolf Run Shoals. [James stays behind to convalesce for a month.]

January 19, 1863 (Camp Fairfax, Virginia)

I am getting along as well as could be expected. It snowed all yesterday and all night and is a foot deep. Oh, it is so lonesome here since the regiment moved. There are 14 of us left sick with 7 left to take care of us.

February 22nd, 1863 (Camp near Wolf Run Shoals)

We are with our regt. Once more. We walked some, rode in a transport wagon part way and an ambulance some over the worst road you ever saw in your life. Started snowing last night, about a foot on the ground and still coming. I’m feeling as good as a colt today.

March 4th, 1863

I feel anxious to hear the proceedings of the town meeting and to know the town officers.

March 10th, 1863

The rebels cut up a right smart caper the other night. They came up to our picket line wearing our uniforms and found what the countersign was, then came through to Fairfax and took General Stoughton and some twenty other prisoners along with about a hundred horses. There was not a gun fired. The General had no business being five miles from his men, he’s probably in Richmond now.

March 14, 1863

You asked if my butter and cheese was gone. It’s been gone some time. You said you would send me more, but I don’t think it best. I don’t think it pays to send stuff and I have to give half of it away or be called a hog and I don’t like that. The money it costs will do more good in some other way.

You may tell Sherman that he needn’t put any dependence on me to help him hay, for I don’t think I’ll do much haying this summer. If I live to get home I shall take things easy.

March 26th, 1863 (Wolf Run Shoals)

March 26th, 1863 (Wolf Run Shoals)

My health is very good excepting a lame back. Oh how I wish this accursed war would end, but we must put our trust in God and wait patiently for the result. We are busy preparing a new campground a half mile away. This one has become quite sickly. Fred Small is sick with the fever. George Parker is better. I don’t think he would have lived if his father hadn’t come out here.

-4-

March 27th, 1863 (Wolf Run Shoals)

We had a dress parade tonight and the brigade band was here and played. I’d like to know what good is a brigade band, all they do is play for the general and sometimes for the regiments on dress parade. They don’t have picket duty, that’s what makes a man feel old, to be out nights on guard. I feel 5 yrs. Older than when I came out, but I don’t care if only I get home safe.

March 31st, 1863 (near Wolf Run Shoals)

The boys have been stockading the new campground, got pretty much ready to move, the fireplace built, ready for the tents to make the roof. Yesterday the order came down to turn the regmt. end for end so they can build a rifle pit on the east end. What a mad set of boys, we tore out our stockade and now it storms so it just sits there all piled up.

Write me how much the listers apprised the sheep and calf. I would be willing to pay my fair share of taxes if only I could be home. I should like to be there to go to the school meeting this evening, but I suppose they will get along without me.

I hope and trust that we shall live to enjoy ourselves yet. I little thought when we were married that we should be separated so soon by the wickedest war ever. I hope right will prevail and soon too for I for one am sick of the way this war is carried on.

April 5, 1863 (near Wolf Run Shoals)

Rosto Turner died this morning of typhoid pneumonia. There is a good many sick in the regmt. Our company is no worse than most, but there ain’t more than fifty (out of 101) that report for duty and a good many of them ain’t fit for duty.

We have more sudden change than in Vermont. One day will be warm and pleasant and the next it will snow like the very mischief. Then it will be warm with mud up to your knees.

April 30th, 1863 (near Wolf Run Shoals)

Lieut. Hammond got a pass for Alexandria so he took the boys money to send by express to his father. I put in thirty-five dollars for you so you will have to go to D. Hammond for it.

Charles Spaulding wrote me that Charles [James’s brother in an Alexandria hospital] is pretty bad off, but I can’t get a pass to see him.

How I would like to be at home plowing and doing spring work. I like farming better than soldiering. It will be a happy day when I can set foot on the soil of Old Vermont. All accounts are the rebs are getting pretty hard up. They have got to give up sooner or later.

May 3rd, 1863 (In the field)

Old Mosby made a raid here this forenoon, they came within a quarter mile of our camp. There were two or three companies of 1st Virginia here. They killed one and wounded quite a number. Our men with the 5th New York rallied on them, killed a good many and wounded a good many more. They wounded Mosby and got his sabre but he got away. We were too late to take any part in the fight. I saw several dead rebs. I tell you, it was a horrid sight to see them laying there all blood and dirt.

May 8th, 1863 (On the banks of the Rappahannock River)

When I came in from picket yesterday morning, we took the cars to this place. Made camp in a clover field and did some pretty tall sleeping.

We have got to where something is going on.

The contrabands [negroes] come in every day. They say the rebs are very short of provisions. It’s amusing to talk to them, some are pretty intelligent considering the chance they have had.

There was seventeen thousand of Hooker’s cavalry camped near us last night. They have been within five miles of Richmond. Their business is to cut off communication, destroy bridges, burn depots and do all the damage they can. You have no idea the amount of property that has been destroyed. I have seen more in the last week than all the time I’ve been here. If you can sell the calf for ten or twelve dollars, I think you should do it.

May 23rd, 1863 (Bristow Station)

We are twenty miles from the Rappahannock now, our brigade is pretty well scattered about. Our duty is to protect the railroad, which is not very hard. We don’t have to drill now, a good thing as it is very hot. Charles is better and got a discharge. We hope to be leaving for Vermont soon. If I live to get out of this, they will have to hitch a pretty strong team to get me back in the army.

-5-

May 24, 1863 (Union Mills)

I like moving on the cars. It is a heap easier than carrying our Government bureaus on our backs.

I must eat my supper. I will tell you what we have had for a change. We have hardtack and coffee for supper and coffee and hardtack for breakfast. Salt port and soft bread occasionally.

June 11, 1863 (Union Mills)

It has been pretty stirring times here for the past few days. Hooker’s army is falling back, the rebs are trying to get to Pennsylvania and Maryland. Last Sunday the troops commenced passing here. I never saw such a sight in my life. I was on picket where I had a fair view of what passed. It was one steady string of Cavalry, infantry, and artillery. They stopped after midnight and started again at three a.m. What this great move will amount to, I don’t know.

June 21, 1863 (Back at Wolf Run Shoals)

There has been heavy cannonading today, but where or what the result, I do not know. Some say there will be another Bull Run battle this summer. If we are needed, they probably will keep us until the 4th, if not we should start for home next Saturday.

The letters home end here, even though James’s enlistment did not end until July 14, 1863. James notes that General Hooker’s Army of the Potomac is hurrying north. They are trying to head off General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, which is planning on taking the war to the North. General George Stannard from Georgia, VT is now commanding the Second Vermont Brigade , having replaced the captured General Stoughton. General Stannard receives orders to follow the main army north at as quick a pace as possible. In his book Nine Months to Gettysburg, Howard Coffin makes great use of letters home and diaries kept by soldiers. He notes that in late June the writing nearly stops as the entire Second Brigade embarks on an eight-day/130 mile forced march from Union Mills, VA to Gettysburg. Mr. Coffin describes how every road north was filled with soldiers. Many were dropping from exhaustion in the 90? heat. It showered hard every day but one, turning the dust to mud. The roadsides were littered with cast-off belongings. Many of the men’s shoes would give out and they would have to march on in socks or barefoot. The men were under strict orders not to break ranks to fill their canteens at wells or streams they passed. As they approached Gettysburg, the 12th and 15th regiments were assigned to guard the corps wagon trains at the rear. The other three regiments continued on to the battlefield.

Coffin says there are many firsthand accounts of the war because of the high literacy level found among Vermonters of the 1860’s.

Les Motschman

Note from Les:

In the first two issues, I encouraged readers to forward to me any information they had about their Hartland ancestors’ Civil War service. I have heard from a few of you and I have been able to update some of the many family connections that Howland Atwood provided in his account of “Hartland in the Civil War” fifty years ago. It is becoming apparent to me that there may not be many HHS members descended from the two hundred men from Hartland who served in the Civil War. However, several readers have told me about their non-Hartland ancestors who were in the Civil War. So now I welcome any accounts of Civil War veterans in your families and will devote a separate section in the newsletters to them. [I already have a very interesting account from a Virginia man who has a second home in Hartland. His ancestor, a Confederate colonel, led an attack at Gettysburg against a position held by the 2nd Vermont Brigade.]

Send info to Les Motschman, 193 Weed Road, Windsor, VT 05089 (or to susanmaple@juno.com.)

-6-

Reprinted from the Hartland Historical Society Newsletter, 2013.