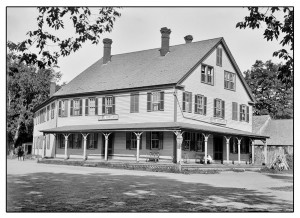

The Pavillion Hotel was on the site of Damon Hall in Three Corners. It was replaced by Damon Hall in 1914.

Pavillion Hotel

Pavillion Hotel looking up Rt. 12 toward Four Corners

Hartland History

posts which are of a specific topic

The Pavillion Hotel was on the site of Damon Hall in Three Corners. It was replaced by Damon Hall in 1914.

Pavillion Hotel

Pavillion Hotel looking up Rt. 12 toward Four Corners

The original round barn was added onto twice, increasing herd size to 150 head. The round barn burned in 1978 and some Milking Shorthorns were lost. The replacement barn was a 100 stall tree stall facility, with attached heifer barn. It was located at Green Acres Farm, the home of Philo Withington in North Hartland.

Hartland Round Barn

Green Acres Farm

Installment 3

Camp Life in Virginia for the “Nine Months Men”

The last HHS newsletter described the formation of the 2nd Vermont Infantry Brigade in response to President Lincoln’s call for 300,000 more volunteers. About four dozen Hartland men responded by joining the 12th or 16th infantry regiments as “Nine Months Men.” By the fall of 1862 these men were in camps in Virginia. I mentioned Camp Vermont as a main camp and while the five regiments of the 2nd Vermont Brigade were all in the same general area south and west of Washington, they occupied several camps along the outer defense line of Washington.

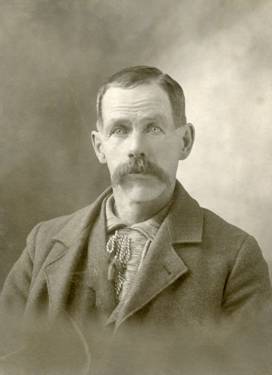

This article will describe in more detail what life in the camps was like for the men who spent most of their service there. This is possible because HHS has a collection of 60 rather lengthy letters written by Pvt. James H. Bowers to his wife Maroa. Pvt. Bowers was 23 when he enlisted from West Windsor and was assigned to Co. A, 12th Vermont Infantry Regiment. James was in the army from 10/4/1862 to 7/14/1863. Several Hartland men were in that 101-soldier company, including William Allen, Oscar Davis, Reuben Lamphear, James Nash, James Rogers, George Spear, and Clinton Willard.

Family records show he and Maroa had been married a year and a half when he enlisted. They had their first child in 1864 and a son, Albert, was born in 1869. Maroa died young, and James married twice more. He died in 1909. Albert moved to Hartland and Albert’s son Jimmy, grandson Eric, and great grandson Scott all live near the Bowers farm, now known as the Flower Farm.

The letters were organized and typed by James’s granddaughter, Rena Jenne Houghton in 1968.

Les Motschman

James Henry Bowers

-1-

October 11th, 1862 (The first letter from Washington includes a pencil sketch of the Capitol Building at the top of the page, below James writes I have been in the United States Capitol.

[Describing the journey from Camp Lincoln in Brattleboro to Washington]:

Marched 3 miles to where we took the cars. Tuesday at 9 o’clock [p.m.] arrived in New Haven at daylight, took a steamboat to New Jersey, then took the cars through Trenton, the capital of New Jersey. Took supper at 8 o’clock in Philadelphia, arrived in Baltimore at 6 o’clock [a.m.] got breakfast at 10 o’clock, took the cars for Washington at 2 o’clock and arrived there 9 o’clock [p.m.] Thursday. The boys stood the journey first rate. If I live to come home, I will tell you all about it. Have you received my bounty?

October 23rd , 1862 (Camp Casey, Capitol Hill)

I am well this morning. O, how I wish I could step in and take breakfast with you. It is quite cold, we have warm days and cold nights. Horrace Houghton died yesterday. Shedd is here, he is going to have his body embalmed, and carry it home.

October 29th, 1862 (Camp Casey, Capitol Hill)

Mr. Hopkins from Windsor died of a fever. The Captain is some better, his wife is here taken care of him.

The nine months men are all here now. It is rumored we might spend the winter in Washington.

Our wagoner, Mr. Brown, got drunk the other day and whipped one of his mules so bad they had to kill him. Brown is in the guard house now.

October 31st, 1862 (Camp Seward, Virginia)

You will see we are in the rebels’ country now. The whole Vermont Brigade marched through the city and over the long bridge into Virginia. I tell you, it was a splendid sight to see those five thousand soldiers all in a mile and a half string. We marched in four ranks with our regiment in the lead.

The land here is very pleasant with good water. It once belonged to the rebel General Lee.

November 3rd, 1862 (Camp near Alexandria, Virginia)

We have moved again. I have not seen a rebel yet except for prisoners. I do not like it here very much. The inhabitants are mostly Negroes. Butter is 36 cents a pound, cheese 20 and apples 3 for 5 cents-so I cannot eat a great deal of such stuff or my money would not hold out. If we are stationed here this winter, you should send me some things. I know it will cost considerable, but I cannot help that. I do not feel I should deprive myself of everything for the sake of making money.

November 18th, 1862 (Camp Vermont, Virginia)

I received a letter from you last night and you had better believe I was glad to hear you was well. My health is first rate. We are busy building our barracks so we can spend the winter here.

First we dig a trench 20 inches deep and a foot wide, then we put split 8-foot white oak logs on end in the ditch and fill around them with dirt to make the walls. When the canvas roof is up, it will look like a house. We are going to plaster the cracks with Virginia mud and if it sticks as well as it does to our boots, it should keep the wind out. I think we can make ourselves very comfortable.

November 26, 1862 (Camp Vermont, Virginia) [Leading up to Thanksgiving Day]

I was glad to hear from you and that you are well. My health is very good. I was glad for the two dollars you sent me for I was entirely out of money. I think we should be thankful that we can hear from one another so often.

Martin had a box of stuff come Monday from Hartland, and then he had some more come tonight in Hammond’s box. I ate the best breakfast of my life this morning. I tell you, Martin is a swell fellow.

I have not the fear that I expected I would. I have been on picket duty twice and have not seen rebels.

-2-

November 30, 1862 (Camp Vermont, Virginia)

We are very busy here nowadays. The 13th, 14th and 15th regiments have left here, leaving only the 16th besides our 12th to do picket duties. We are sometimes sent out four or five miles from camp. There are two or three men stationed at a post. We stay at a post for 8 hours. When relieved we put our rubber blanket on the ground and our woolen blankets over us and sleep just like a pig.

December 7th, 1862 (Camp Vermont, Virginia)

We bought a little box stove for our house. It has an oven so we can bake potatoes or warm up chicken pies or turkey and fixings.

One man from our company is going home. Mr. Lamphere from Hartland died this morning of brain fever.

The boys had whiskey dealt out to them yesterday, but I did not drink any.

December 13th, 1862 (Camp near Fairfax Court House, Virginia)

You will see that the whole brigade has moved from Camp Vermont. It came pretty tough for us to leave our barracks we had just fixed up for winter. The army is moving forward and we have to move up to take the place of those who have gone forward.

I learnt this morning that General Burnside has burnt Fredericksburg and is marching on Richmond.

January 3rd, 1863 (Camp Fairfax, Virginia)

A very pleasant day here today. I done my washing this forenoon. A lot of us went down to the brook and built a fire and het up some water for washing. I do not believe in washing Saturday, but we have to wash when we have the chance.

We have our tent stockaded so it’s as comfortable as our barracks at Camp Vermont.

You say you have 6 sheep. I think the sheep and calf would eat what hay I got up.

January 9th, 1863 (Camp Fairfax, Virginia)

We shall have all the fighting we want, but that is what we came for. If I ever go into battle, I hope I shall be able to do my duty and if I fall, I hope to die in a good cause, but I fear the disease in camp more than I do the enemy’s balls.

You should send me some letter stamps if you can get them. What have you done with the hog money?

January 12th, 1863 (Camp Fairfax, Virginia) [after receiving butter]

I tell you, Maroa, that is the best butter I ever eat in my life. I make a cup of tea and then put in a piece of butter and crumble in my hard crackers and it goes first rate.

I get your letters the third day after they are mailed. We get the Journal [Windsor paper?] every Monday night. That is quicker than we used to get it at home sometimes.

We have plenty of company now days. What’s left of a brigade of PA. Buck Tails came in here the other night. It is interesting to hear them tell what they been through. They have seen hard service, I think 13 battles. The last they was in was Fredericksburg where they were cut up pretty bad. They were in the 7 Days fight before Richmond, also Antietam, and South Mountain, and Bull Run. They have lost their knapsacks and blankets four times and had to pay for new ones. They are smart as steel but have been out so long they are pretty rough.

January 18th, 1863 (Camp Fairfax, Virginia)

A letter from Martin (Herrick):

I write you at the request of your husband as he and Charley [James’s brother] are sicke with the measles. I think they are doing as well as can be expected. I will sit with them tonight. I don’t want you to worry, they have good care.

January 19th – The boys rested very well. I think they will soon get up again.

Martin

-3-

The regiment moved ten miles to Wolf Run Shoals. [James stays behind to convalesce for a month.]

January 19, 1863 (Camp Fairfax, Virginia)

I am getting along as well as could be expected. It snowed all yesterday and all night and is a foot deep. Oh, it is so lonesome here since the regiment moved. There are 14 of us left sick with 7 left to take care of us.

February 22nd, 1863 (Camp near Wolf Run Shoals)

We are with our regt. Once more. We walked some, rode in a transport wagon part way and an ambulance some over the worst road you ever saw in your life. Started snowing last night, about a foot on the ground and still coming. I’m feeling as good as a colt today.

March 4th, 1863

I feel anxious to hear the proceedings of the town meeting and to know the town officers.

March 10th, 1863

The rebels cut up a right smart caper the other night. They came up to our picket line wearing our uniforms and found what the countersign was, then came through to Fairfax and took General Stoughton and some twenty other prisoners along with about a hundred horses. There was not a gun fired. The General had no business being five miles from his men, he’s probably in Richmond now.

March 14, 1863

You asked if my butter and cheese was gone. It’s been gone some time. You said you would send me more, but I don’t think it best. I don’t think it pays to send stuff and I have to give half of it away or be called a hog and I don’t like that. The money it costs will do more good in some other way.

You may tell Sherman that he needn’t put any dependence on me to help him hay, for I don’t think I’ll do much haying this summer. If I live to get home I shall take things easy.

March 26th, 1863 (Wolf Run Shoals)

March 26th, 1863 (Wolf Run Shoals)

My health is very good excepting a lame back. Oh how I wish this accursed war would end, but we must put our trust in God and wait patiently for the result. We are busy preparing a new campground a half mile away. This one has become quite sickly. Fred Small is sick with the fever. George Parker is better. I don’t think he would have lived if his father hadn’t come out here.

-4-

March 27th, 1863 (Wolf Run Shoals)

We had a dress parade tonight and the brigade band was here and played. I’d like to know what good is a brigade band, all they do is play for the general and sometimes for the regiments on dress parade. They don’t have picket duty, that’s what makes a man feel old, to be out nights on guard. I feel 5 yrs. Older than when I came out, but I don’t care if only I get home safe.

March 31st, 1863 (near Wolf Run Shoals)

The boys have been stockading the new campground, got pretty much ready to move, the fireplace built, ready for the tents to make the roof. Yesterday the order came down to turn the regmt. end for end so they can build a rifle pit on the east end. What a mad set of boys, we tore out our stockade and now it storms so it just sits there all piled up.

Write me how much the listers apprised the sheep and calf. I would be willing to pay my fair share of taxes if only I could be home. I should like to be there to go to the school meeting this evening, but I suppose they will get along without me.

I hope and trust that we shall live to enjoy ourselves yet. I little thought when we were married that we should be separated so soon by the wickedest war ever. I hope right will prevail and soon too for I for one am sick of the way this war is carried on.

April 5, 1863 (near Wolf Run Shoals)

Rosto Turner died this morning of typhoid pneumonia. There is a good many sick in the regmt. Our company is no worse than most, but there ain’t more than fifty (out of 101) that report for duty and a good many of them ain’t fit for duty.

We have more sudden change than in Vermont. One day will be warm and pleasant and the next it will snow like the very mischief. Then it will be warm with mud up to your knees.

April 30th, 1863 (near Wolf Run Shoals)

Lieut. Hammond got a pass for Alexandria so he took the boys money to send by express to his father. I put in thirty-five dollars for you so you will have to go to D. Hammond for it.

Charles Spaulding wrote me that Charles [James’s brother in an Alexandria hospital] is pretty bad off, but I can’t get a pass to see him.

How I would like to be at home plowing and doing spring work. I like farming better than soldiering. It will be a happy day when I can set foot on the soil of Old Vermont. All accounts are the rebs are getting pretty hard up. They have got to give up sooner or later.

May 3rd, 1863 (In the field)

Old Mosby made a raid here this forenoon, they came within a quarter mile of our camp. There were two or three companies of 1st Virginia here. They killed one and wounded quite a number. Our men with the 5th New York rallied on them, killed a good many and wounded a good many more. They wounded Mosby and got his sabre but he got away. We were too late to take any part in the fight. I saw several dead rebs. I tell you, it was a horrid sight to see them laying there all blood and dirt.

May 8th, 1863 (On the banks of the Rappahannock River)

When I came in from picket yesterday morning, we took the cars to this place. Made camp in a clover field and did some pretty tall sleeping.

We have got to where something is going on.

The contrabands [negroes] come in every day. They say the rebs are very short of provisions. It’s amusing to talk to them, some are pretty intelligent considering the chance they have had.

There was seventeen thousand of Hooker’s cavalry camped near us last night. They have been within five miles of Richmond. Their business is to cut off communication, destroy bridges, burn depots and do all the damage they can. You have no idea the amount of property that has been destroyed. I have seen more in the last week than all the time I’ve been here. If you can sell the calf for ten or twelve dollars, I think you should do it.

May 23rd, 1863 (Bristow Station)

We are twenty miles from the Rappahannock now, our brigade is pretty well scattered about. Our duty is to protect the railroad, which is not very hard. We don’t have to drill now, a good thing as it is very hot. Charles is better and got a discharge. We hope to be leaving for Vermont soon. If I live to get out of this, they will have to hitch a pretty strong team to get me back in the army.

-5-

May 24, 1863 (Union Mills)

I like moving on the cars. It is a heap easier than carrying our Government bureaus on our backs.

I must eat my supper. I will tell you what we have had for a change. We have hardtack and coffee for supper and coffee and hardtack for breakfast. Salt port and soft bread occasionally.

June 11, 1863 (Union Mills)

It has been pretty stirring times here for the past few days. Hooker’s army is falling back, the rebs are trying to get to Pennsylvania and Maryland. Last Sunday the troops commenced passing here. I never saw such a sight in my life. I was on picket where I had a fair view of what passed. It was one steady string of Cavalry, infantry, and artillery. They stopped after midnight and started again at three a.m. What this great move will amount to, I don’t know.

June 21, 1863 (Back at Wolf Run Shoals)

There has been heavy cannonading today, but where or what the result, I do not know. Some say there will be another Bull Run battle this summer. If we are needed, they probably will keep us until the 4th, if not we should start for home next Saturday.

The letters home end here, even though James’s enlistment did not end until July 14, 1863. James notes that General Hooker’s Army of the Potomac is hurrying north. They are trying to head off General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, which is planning on taking the war to the North. General George Stannard from Georgia, VT is now commanding the Second Vermont Brigade , having replaced the captured General Stoughton. General Stannard receives orders to follow the main army north at as quick a pace as possible. In his book Nine Months to Gettysburg, Howard Coffin makes great use of letters home and diaries kept by soldiers. He notes that in late June the writing nearly stops as the entire Second Brigade embarks on an eight-day/130 mile forced march from Union Mills, VA to Gettysburg. Mr. Coffin describes how every road north was filled with soldiers. Many were dropping from exhaustion in the 90? heat. It showered hard every day but one, turning the dust to mud. The roadsides were littered with cast-off belongings. Many of the men’s shoes would give out and they would have to march on in socks or barefoot. The men were under strict orders not to break ranks to fill their canteens at wells or streams they passed. As they approached Gettysburg, the 12th and 15th regiments were assigned to guard the corps wagon trains at the rear. The other three regiments continued on to the battlefield.

Coffin says there are many firsthand accounts of the war because of the high literacy level found among Vermonters of the 1860’s.

Les Motschman

Note from Les:

In the first two issues, I encouraged readers to forward to me any information they had about their Hartland ancestors’ Civil War service. I have heard from a few of you and I have been able to update some of the many family connections that Howland Atwood provided in his account of “Hartland in the Civil War” fifty years ago. It is becoming apparent to me that there may not be many HHS members descended from the two hundred men from Hartland who served in the Civil War. However, several readers have told me about their non-Hartland ancestors who were in the Civil War. So now I welcome any accounts of Civil War veterans in your families and will devote a separate section in the newsletters to them. [I already have a very interesting account from a Virginia man who has a second home in Hartland. His ancestor, a Confederate colonel, led an attack at Gettysburg against a position held by the 2nd Vermont Brigade.]

Send info to Les Motschman, 193 Weed Road, Windsor, VT 05089 (or to susanmaple@juno.com.)

-6-

Reprinted from the Hartland Historical Society Newsletter, 2013.

HARTLAND IN THE CIVIL WAR

(Fourth Installment, June, 2013)

by Les Motschman

The last installment in this series comprised firsthand accounts of camp life in Virginia as experienced by the “Nine Months” men of the Second Vermont Infantry Brigade. I enjoyed reading the 60 letters Pvt. James Bowers wrote to his young wife, Maroa. I thought they gave good insight into how the men were spending their time, their thoughts about the war and home, and how they coped with the danger posed by not just the rebs but also the ever-present threat of disease. While working on that issue, I was trying to acquire copies of the “Hammond” letters Howard Coffin cites several times in Nine Months to Gettysburg and refers to in his latest book Something Abides: Discovering the Civil War in Today’s Vermont. Coffin thanks long-time Hartland resident Sidney Hammond for giving him copies. I received the copies from Sid’s son, John, just as I finished the last issue, so I will write a little about them now.

The 44 Hammond letters are mostly from 20-year-old Jabez writing to his father, Dan, in West Windsor. Three are from Dan to Jabez, wanting to know everything that his “four little boys were doing in the Great Big War.” There were four Hammond brothers in Co. A of the 12th Vermont Infantry Regiment. Ira was the oldest at 27; as a teamster, his duties were different from those of most of the men. Pvt. Bowers in his letters referred to a “Lieutenant Hammond,” who would have been 26-year-old Stephen. Harler was the next in age, and Jabez, the youngest, was a corporal. His duties included making up the details for picket duty and guard duty at the camp. Dan refers to his sons by several nicknames, and Sid wrote that he didn’t always know who was who. Jabez sometimes signed as Bogus; other names were Lightfoot, Scratchass, Deacon, and The Orderly.

Both Bowers and Hammond wrote a lot about their health and how others in the company were doing. In return, the letters from home included health updates on the family members and neighbors. I think people must have been very thankful when they were enjoying good health because they knew when they weren’t feeling well it could turn into something serious, especially in the camps. Surprisingly, another topic both men wrote a lot about, especially when spring came, was when they would head back to Vermont. It seems to have been a major topic of discussion in camp. They weren’t sure if their nine months started when they enlisted, or left home for Brattleboro, or were sworn into the U. S. Army. Both men mentioned late May as a possible end of their service. Their last letters around the middle of June when they were aware some big battle might be shaping up, indicated they were sure July 4th was the last day the Army could keep them. Both men repeated rumors either that they might be released early or that the Army wouldn’t let them go in the middle of the “fighting season” and they would involuntarily be extended three to six months. July 14, 1863, was in fact the day the men in the 12th Vermont Regiment were mustered out of the Army.

Sid Hammond first encountered the packet of letters in his grandmother’s bureau drawer, as an eleven-year-old interested in stamp collecting. He was told he must not tamper with them in any way. Home from college in 1949, Sid noticed that his father, confined to bed with an illness, was reading them. Sid spent many hours that summer transcribing them into typewritten pages to make them easier to read.

When he had five children of his own, they used the typed letters for reports and term papers at school. Sid did not see the original letters again until 1982, when he learned another Hammond family had them. They

-1-

gave the letters to Sid, and he went to work again to decipher the handwriting and the sometimes confusing capitalization and punctuation. He created the fine 60-plus page folder I enjoyed spending a few hours with, a welcome addition to the Hartland Historical Society.

Sid was Jabez Hammond’s great-grandson. Sid owned a farm on Mace Hill Rd. near the center of town. Sid’s son John now owns the farm, and John’s son Jabez Hammond lives there. Sid died in 2000.

[These letters are available to read at vermontcivilwar.org/units/12/Hammond.php. You will see a description, and then can click on the dates for individual letters.]

Chancellorsville Campaign

The second issue in our Civil War series ended with the disastrous Union defeat at Fredericksburg, Virginia, on December 13, 1862. Both the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia remained in the Fredericksburg area for the winter. President Lincoln relieved Gen. Burnside of his command January 25, 1863. He was replaced by one of his corps commanders, Gen. Joseph Hooker, who worked through the winter to restore morale and get his army ready for a spring offensive. By the end of April, Gen. Hooker had the best equipped army yet as well as a plan to divide his forces and trap Gen. Lee’s rebel army. The battle of Chancellorsville was a series of battles from May 1st to 6th, 1863.

First, in an attempt to distract Lee, Gen. John Sedgwick took the First and Sixth Army Corps across the Rappahannock near Fredericksburg, and made another assault on Marye’s Heights, site of the worst fighting in December. Attack after attack was repulsed, but the Confederate force wasn’t as large as before, so by noon Sedgwick’s forces broke through and headed for Chancellorsville ten miles away. The 1st Vermont Infantry Brigade was attached to the First Corps, so Hartland men in the 3rd, 4th and 6th regiments were at Marye’s Heights. Corp. Roderick Bagley was wounded and taken prisoner there May 3. He was paroled June 23 but didn’t return to the 3rd Vermont.

As Sedgwick’s troops moved to the rear of Lee’s forces, they encountered a Confederate division at Salem Heights, sent to beat back the Union threat. The Vermont 3rd, 4th, and 5th regiments fought there, while the 6th did gallant service at nearby Bank’s Ford. There the 6th drove back the rebs and took 250 prisoners. Samuel Jones was wounded there May 4.

Meanwhile, Gen. Hooker, with the main Union force, was trying to circle Lee’s army, unfortunately without adequate reconnaissance from the cavalry. They found themselves in an area known as The

Wilderness, a country of stunted, scrubby holly and cedar trees tangled in webs of vine and briars. Gen. Hooker called a halt near Chancellorsville as they could not see the enemy. Confederate Generals J.E.B. Stuart and Stonewall Jackson knew the country well, so they engaged the Union in battle for four days.

It was horrible fighting in the thickets. Cannons belched grapeshot and canister at close range, setting the

woods on fire. The screams of the wounded as the fire approached were reportedly beyond description. Sedgwick and Hooker retreated across the river. Hooker lost 17,000 men. Lee lost 13,000, including his favorite General, Stonewall Jackson, who was shot by his own men while he was checking the lines at dusk.

[These accounts of the Battle of Chancellorsville are mostly from Howland Atwood’s notebook where he cites The Compact History of the Civil War.]

-2-

Chancellorsville was the last of a series of Union failures in Virginia, after each of which Lincoln changed commanders. Gen. Burnside’s whiskers inspired the term “sideburns.” It is said that Gen. Hooker’s name was appropriated to describe a certain kind of camp follower, a term that is still in use today. The Gen. Hooker equestrian statue guards the Hooker entrance to the Massachusetts State Capitol in Boston.

I have been to Fredericksburg twice. Like most battlefield parks, it has been preserved or restored to look as it did before the battle. It’s a beautiful, peaceful place. You can walk the broad slope where tens of thou- sands of Union troops attacked in wave after wave. Thousands fell there, killed or wounded. Above you are the stone wall and sunken road defended by rebel infantry. From atop the hill called Marye’s Heights, the Confederate artillery rained fire on the open field. I wondered, as most men would, what was it like to have been there? What would I have done? As a noncombant Marine with several weeks of infantry training, I know something about discipline, following orders, and unit cohesiveness–but no one of us knows how we would perform in combat until tested. I think Pvt. Bowers speaks for most men when he wrote to his wife, “If I ever go into battle, I hope I shall be able to do my duty, and if I fall I hope to die in a good cause.”

War has always been part of human history and shows no sign of abating. Clans, sects and countries often take up arms to settle their differences. What draws men to fight? A little piece in the Vermont Civil War Sesquicentennial Visitor Guide gives some insight.

In June of 1863, Maj. Richard Crandall was home on leave from the 6th Vermont Regiment. He and a friend camped on the summit of Mt. Ascutney. On that early summer evening, Crandall talked of being part of Gen. John Sedgwick’s attack at Second Fredericksburg and remarked, “Oh, to have lived a minute then was worth a thousand years.” Crandall was killed by a sharpshooter in the Cold Harbor trenches a year later.

Gettysburg

The biggest battle ever fought in the Western Hemisphere

Books, reports, and accounts of the Battle of Gettysburg abound. The three-day battle on July 1st, 2nd, and 3rd, 1863, was the biggest of the Civil War. In Gettysburg are the largest number of monuments of any Civil War battlefield, marking the spots where units served or officers fell. Gettysburg is the most visited Civil War battlefield; tourists have gone there since the smoke cleared. In 2013, the 150th year since the battle, tens of thousands of re-enactors and about 200,000 visitors are expected in the weeks just before and after the battle dates.

Maintaining my theme, I will not try to describe the entire massive battle, instead concentrating on where Hartland men were. I will make a couple of exceptions though, for some Vermont units without Hartland men that earned everlasting glory for little Vermont at pivotal points in the battle that turned out to be the pivotal battle of the whole War. The Civil War exhibit at the Vermont Historical Society building in Barre indicates that 11 Vermont regiments were at Gettysburg where the 13th, 14th, and 16th Regiments and the 1st Cavalry saw most of the action.

In his 1960 book Civil War, Bruce Catton writes that Chancellorsville was Gen. Lee’s most brilliant victory, but won at a heavy cost. Lee knew he was winning the battles but losing a war of attrition. Lee’s army numbered just 60,000 at Chancellorsville, half of “Fighting Joe” Hooker’s army. If not for Hooker’s caution

-3-

and unfamiliarity with the terrain, the Confederate army might have been crushed. Lee decided to mount another daring raid on the North while he still could. A major decisive Union defeat in Pennsylvania would so alarm the populace in the North that it might bring an end to the war on terms favorable to the South. Lee knew if he lost in Union territory, he might very well lose his army and the war.

President Lincoln was devastated by Hooker’s loss. Hooker wanted to make another move on Richmond. Lincoln said “No, Lee’s army must be the ‘objective point.’ ” Federal columns started north in pursuit of Lee’s invading army. It was certain that the two armies would soon meet again in a full battle. Lincoln thought Hooker was the wrong man to have in command, so on June 28 he replaced him with Maj. Gen. George Meade, a corps commander. Gettysburg seemed like a likely battle site as roads from all directions converged there. Lee’s Southern army approached from the north. Meade’s Northern army approached from the south.

Also on June 28, the Vermont First Cavalry Regiment was attached to the U. S. Cavalry. As the cavalry gained experience, it became a better match for Confederate Gen. J. E. B. Stuart’s daring, skilled horsemen. The Vermont Humanities Council’s weekly Civil War paper of June 7 states that the Gettysburg Campaign started with the Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863. The Union Cavalry discovered that Lee’s army was on the move. Brandy Station was the largest cavalry battle of the war and both sides had hundreds of casualties. Stuart was deeply embarrassed that the Union attack had taken him by surprise.

As reported earlier, one of the main cavalry functions was to provide information to commanders on the enemy’s strength and position. Gen. Hooker had just suffered a terrible defeat because he sent his army into battle not fully knowing the terrain or the enemy’s exact strength and location. The Union cavalry was away trying to destroy railroads above Richmond in an effort to cut off supplies to the Confederate Army. Just a few weeks later, it was Lee’s turn to be maneuvering blind. When the invading army entered Pennsylvania, Lee’s three infantry corps and cavalry were widely separated. Their presence had the desired effect as it caused widespread panic. Yet, with J. E. B. Stuart’s cavalry raiding well to the east, Lee did not know that the Union army had left Virginia and was closing fast on him. As all roads led to Gettysburg, that was the handiest place to concentrate his forces.

July First

The first Confederate troops to enter Gettysburg were looking for shoes. They encountered Union cavalry there and skirmished with them. As more troops from both armies poured in, the fighting intensified. The Confederates pushed the Union forces out of the town and formed a defensive line along Seminary Ridge.

When the battle opened, the Sixth Army Corps, including the First Vermont Brigade with several Hartland men, was still in Maryland 30 miles away. That evening, they started for Gettysburg. Gen. John Sedgwick gave his famous order to “put the Vermonters ahead and keep the column well closed.”

Meanwhile, the Second Vermont Brigade led by hard-driving Gen. Stannard, had stopped for the night at Emmitsburg, Maryland. Stannard received an order from Gen. John Reynolds, Commander of the First Army Corps, to hasten to join him as he was nearing Gettysburg and expected to be attacked that day. The weary Vermonters, including about three dozen Hartland men who had been marching for six days, hit the road. Soon, orders were received to detail the 12th and 15th to guard the First Corps wagon train. The majority of Hartland men were in the 12th, so they would not be engaged in the great battle. The 13th, 14th, and 16th arrived the evening of the first day of the bloody battle. The First Corps had entered the battle as soon as they arrived. Gen. Reynolds was killed. The Union troops were forced to give ground until Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock took command and rallied Union forces to retake some lost ground.

-4-

The fighting had died down for the night and most of the Second Vermont Brigade was told to sleep on the ground in full dress with their rifles by their sides. One third of the 16th was assigned picket duty. Those 200 men spent a warm and fearful night among the dead and wounded on the battlefield between the armies. Seven Hartland men in Co. H of the 16th were Charles Alexander, Thomas Benjamin, William Dodge, Charles S. Gardner, Thomas Lenehan, Lewis J. M. Marcy, and Thomas Tracy. They would have been the ones fighting at Gettysburg. Benjamin and Gardner were wounded July Third.

July Second

When Gen. Meade arrived with the main Union army, the Federal forces immediately seized Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge, and Culp’s Hill. As more Union forces entered the battlefield, the nearly three-mile Union line took the shape of a giant fishhook. The 1,500 soldiers in the Second Vermont Brigade found themselves to be near the center of the line somewhat to the rear, close to Gen. Meade’s headquarters. The Hartland men in the 12th accompanied the Corps wagon train to Rock Creek Church, about two and a half miles from the battlefield. Company B, which included 26 Hartland men, was sent forward to guard the ammunition wagons at the edge of the battlefield.

The fighting was mostly on the right and left flanks of the Union line. The fighting on the left was especially fierce, with hundreds of casualties. The Union line was getting thin in places. Late in the day, Lee sent even more troops against the blue line in an attempt to roll it towards the center and possibly break through. A Minnesota regiment was brought to the line and quickly lost four-fifths of its men. The three regiments of the Second Vermont Brigade were still resting on Cemetery Hill. They formed up and marched at double quick a mile down the Tanneytown Road to where the battle was loudest. As soon as the Vermonters leading the First Corps crested the ridge, they were in the thick of the battle, firing and taking fire. The Union line held and the second bloody day of the battle ended. That night, men from the 16th were again sent out onto the battlefield to do picket duty among the dead and dying. The 13th and 14th dug in along the line to make their position more secure for the battle that would surely take place the next day.

The seasoned Vermonters of the First Brigade came in at the head of the 15,000-man Sixth Corps near the end of the fighting. The exhausted troops were deployed at the extreme left of the Union line to replace men lost in the day’s fighting. The “Old Brigade” would not have to fight at Gettysburg.

July Third

As another hot day dawned, the Confederates attacked Culps Hill on the right end of the Union line. The Second Vermont Brigade took occasional cannon fire. One shot hit an ammunition wagon and killed or wounded several men of the 14th. Mid-morning, the Confederates called off the attack and quiet settled over the battlefield. After noon, the men could see movement along Seminary Ridge a mile away across the open battlefield. At one o’clock, a single cannon shot signaled 150 Confederate cannon along a two-mile line to commence firing. When Federal cannon joined in, over 275 cannon were engaged in a great artillery duel. Lt. Benedict, an aide to Gen. Stannard, described it: “The air seemed filled with flying missiles. Shells whizzed and popped on every side. Spherical case exploded over us and rained down iron bullets. Canister hurtled around us and round shot plowed up the ground.”

Howard Coffin in Nine Months to Gettysburg says the men of the Second Brigade laid face down on the ground under a hot mid-day sun during the artillery barrage which lasted over two hours. Many men were wounded by shrapnel, and some were killed, but as Cemetery Ridge is only a gentle rise, many of the shells passed over the front lines and landedfar in the rear. The fire wreaked havoc on supply wagons and support troops. Many horses were maimed or killed. At Gen. Meade’s headquarters, an orderly serving lunch was torn in half by a shell. The men of the 16th still out on the field on picket were in the safest place as shot from both sides sailed over them. Incredibly, there were reports that many men lying in the hot sun were lulled to

-5-

sleep by the constant din. Through it all, Gen. Stannard and his staff stood erect or walked among the lines.

Around 3 p.m., Union cannons let up. Soon the Confederates stopped shelling as well. The silence was awesome. Men woke up, the wounded were taken to the rear, and officers checked their men. The Vermonters seemed to be in good condition. They understood that the intense fire directed at them near the Union center was a prelude to an infantry attack. Remember that the entire Second Brigade was made up of Nine Months men whose enlistments were just about up. The men in the 12th would be back in Vermont in less than a week. One can only imagine how many prayers they offered up from the battlefield that day. If they could just get through this battle, they’d be headed home.

As the smoke cleared from the battlefield, Vermonters could see long ranks of gray-clad soldiers emerging from the rebel line, battle flags unfurled and bayonets gleaming. Lee had ordered more than 12,000 men to attack the middle of the long Union line. Major General George Pickett and 5,000 Virginians led the charge. Union cannon opened fire and blew holes in the gray ranks, but still they came at a quick pace. No officer had to give the men of the 16th an order to leave the picket line; they rose, fired once, and ran to the Union lines. Gen. Stannard ordered the men not to fire until the rebs were near. The broad line of attack seemed to be focused on a small copse of trees to the Vermonters’ right as the whole mass of confederates veered that way. Now the rebels were passing across the front of the Vermont regiments at a distance of a thousand feet. The 14th rose and let loose a volley followed by the 13th.

The volleys did damage to the rebel attack, but some had breached the Union line and headed for the cannons. Gen. Stannard saw an opportunity and gave what Coffins calls “the order of his life and maybe of the whole war.” He ordered the 13th and 16th to form up on the field and make a line so they could fire at short range directly into the Confederate flank. The Vermonters were not experienced in battle, but they had spent many hours in camp drilling. They jogged in formation a hundred yards down the field to get closer to the rebs and then executed a complex drill maneuver peeling off company by company to quickly form a 900-man firing line close to the rebel flank. The field was littered with Confederate casualties, but their soldiers were still pressing the center of the Union line hard, with bayonet fighting along Cemetery Ridge.

The Vermonters fired no more than 8 to 12 rounds, but every bullet took effect at such short range. Some of the attackers turned on the Vermonters. The Confederates were taking canister fire at their front and musket fire on three sides. Finally, rebs were throwing down their guns and running towards the Vermonters to surrender. Colonel Randall, the 13th’s commander, ran in front of his men ordering them to cease fire, and then directed the rebs into his lines, thus saving many Southern lives.

Where Confederate troops engaged Union defenders on Cemetery Ridge is considered the “High Water Mark of the Confederacy.” The repulse of Pickett’s Charge dashed the South’s hopes of a great victory on Northern soil. Although the War would last almost another two years, the momentum was now with the Union. The next day, July Fourth, Vicksburg, 1,000 miles away, was surrendered to Gen. U. S. Grant. The Union now controlled the entire Mississippi River.

Late in the battle, Gen. Stannard was wounded but, he stayed on the field until the end of the fighting. He is credited as the first Vermonter to volunteer when war was declared. In 1867 the Vermont Legislature named a town in his honor. His statue stands atop on a very tall column on the battlefield where he commanded the Second Vermont Brigade. The Second Vermont suffered 46 killed, 240 wounded, and 56 missing. Some wounded died weeks later in Vermont and some veterans suffered physical or mental disability for years.

Also late in the battle, the 1st Vermont Cavalry, then part of the U. S. Cavalry, participated in an ill-conceived charge with five killed, 16 wounded and 55 missing. This may have been where Hartland’s Capt. Oliver Cushman was wounded. Cushman left Dartmouth early in the war to join the Cavalry. The Cushmans lived on what is now known as the Hoisington Farm.

-6-

July Fourth

The exhausted troops of the 13th, 14th, and 16th were told to go and sleep in the rear. It started raining in the night and accounts indicate most men slept for hours lying on the ground in the pouring rain. Gen. Lee prepared his army to be attacked. True to form, the Union Commander, Meade, did not think his army was in good enough shape to press Lee. The Confederates started slipping away toward the Potomac. After hearing from President Lincoln, Meade mounted a half-hearted pursuit. Lee’s 17-mile-long train consisted of not only the army and its supplies, but also 10,000 animals accumulated from Pennsylvania farms as well as Union prisoners. The train’s progress was stalled at the Potomac crossing, where the troops set up a strong defensive position. The Union force sent to pursue encountered the Confederates on July 10th. The Third Infantry Regiment was on the front line of a fierce fight known as the Battle of Funkstown. Hartland soldier Thomas Leonard was wounded there. The Army of Northern Virginia returned to Virginia able to fight another day.

In describing where Vermonters were at Gettysburg, I have used Howland Atwood’s notebook, and of course Howard Coffin’s Nine Months to Gettysburg. Coffin says he wrote Nine Months because he didn’t think Vermonters get enough credit in the history books for the important work they did there. I have also referred to Coffin’s first book, Full Duty. I have the book that was Coffin’s main source for Nine Months, the 900-page History of the 13th Regiment, Vermont Volunteers, which Coffin calls one of the best regimental histories from the Civil War. Pvt. Ralph Sturtevant spent his whole life writing this history and gathering individual accounts and pictures of the nearly 1,000-man 13th Regiment. My great-grandfather, Marcus Best, from the northwestern Vermont town of Highgate was a tentmate of Sturtevant’s and was in an Alexandria hospital at the time of Gettysburg. The book was published nearly 50 years after Gettysburg and a couple years after Sturtevant’s death.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In the last issue, I indicated I would like to hear about your Civil War ancestors, even if they are not connected to Hartland. The newsletters will end with whatever HHS members give me to share with you.

I’ll go first. I mentioned Marcus Best above. Sturtevant writes that the fever Best had in camp affected him the rest of his life. Still, he was a farmer and ran a store for a while. He also had seven children with three wives. The youngest, my grandfather, Guy Best, came with Marcus when he moved to Reading late in life. Guy Best lived in Hartland his entire adult life.

Life-long Hartland resident Edith Barrell White has two connections to the Hartland Roster. Perry Lam-phere was her grandfather, John F. Barrell’s half-brother. Lamphere was in the 6th Vermont Infantry Regt. From October 15, 1861 to January 1, 1864. He died of disease in New York City and is buried in the Hartland Village Cemetery. John F. Barrell’s oldest brother, Hubbard, went to the Civil War from Connecticut. Another brother, Edgar Barrell, enlisted October 19, 1861 in the 6th New Hampshire. Infantry Regt. From Plainfield, He was wounded at Second Battle of Bull Run, August 29, 1862.

-7-

The other Hartland connection is that John F. Barrell’s oldest sister married Oscar Davis, one of the Davis twins in the 12th Vermont Infantry Regiment. Although a “Nine Months’ Man,” he served only six months, so he would have missed the long march and Gettysburg. [Thanks, Edith, for this information.]

A Southern Family in the Civil War

[A Southern Family in the Civil War was submitted by Fielding L. Williams of Richmond, Virginia and Hartland, Vermont.

The Civil War had a tragic impact on families on both sides. Juxtaposed against stories of Hartland families are stories of southern families, such as that of Lewis B. Williams. In 1861 he was a lawyer in Orange, Virginia, in practice with his son, Lewis B. Williams, Jr., age 28, a graduate of Virginia Military Institute.

By early 1861 seven Southern states had seceded from the Union. Virginia was not one of them and was undecided as to what course to follow. The Virginia legislature called for an election of delegates to a special convention to decide whether Virginia should secede. Lewis Williams was opposed to secession and ran as a delegate in support of the Union. He was defeated by a secessionist candidate.

The delegates convened in Richmond, Virginia, on February 13. After weeks of debate, and despite the secession of other states, on April 4, by a vote of 90 to 45, the delegates voted that Virginia should not secede. Eight days later, on April 12, the Confederacy attacked Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. Still Virginia failed to act. Then, on April 15, President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers from all states to put down the rebellion. This meant Virginia must turn against sister Southern states, and it aroused anti-unionism to the point that, on April 17, the convention approved Virginia’s secession by a vote of 88 to 55.

Lewis Williams, Jr., immediately joined the Confederate army and was appointed a Captain in the 13th Virginia Infantry Regiment. Wounded, captured and released in 1862, he rose to the rank of Colonel, and on July 3, 1863, he commanded the 1st Virginia Regiment at Gettysburg in the attack on Union positions known as Pickett’s Charge. Because he was ill on that day, he was granted permission to ride a horse as he led his troops in the attack, making him an especially vulnerable target. As he crossed the field, he was struck by a shell that severed his spinal cord, and when he fell from his horse, he landed on his drawn sword. He died after four days of agony and was buried on the battlefield.

Burial of Confederate dead at Gettysburg was understandably haphazard. There were more than 3,000 bodies to be dealt with. Unlike the Federal dead who were reburied in a special battlefield cemetery, the Confederates, regarded as traitors by the Federal Government, were left in shallow graves or trenches. Their ultimate removal and reburial is a story in itself. Colonel Williams’ body was shipped to Baltimore by friends in 1863 and later, in 1896, was removed to Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia, and was buried next to General George Pickett.

Lewis Williams, the father who had ardently opposed Virginia’s leaving the Union, had subsequently become a loyal supporter of the Confederate cause and lost to it his beloved namesake.

The havoc caused by the Civil War is very sad, but there is consolation in the perspective of historian Shelby Foote: Before the war it was always “the United States are.” After the war it became “the United States is.” It made us one.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Thanks to Susan Motschman for typing and layout and to Pat Richardson for help editing.

-8-

SMITH, David M., inventor, born in Hartland, Vermont, in 1809; died in Springfield, Vermont, 10 November, 1881. He began to learn the carpenter’s trade in Gilsum, New Hampshire, when he was twelve years old, and seven years later taught in a school. Subsequently he began the manufacture of “awls on the haft,” for which he obtained a patent in 1832. The awl-haft as manufactured by him was similar if not identical with the one now known as the Aiken awl. In 1840-’1 he represented the town of Gilsum in the New Hampshire legislature, after which he removed to Springfield, Vermont He patented a combination-lock in 1849, of which an English expert named Hobbs, who had opened all the locks that were brought to him in London, said : ” It cannot be picked.” This lock he also patented in England, and about this time he invented an improvement on the first iron lathe dog that is now in common use. He also devised a peg-splitting machine, and two sewing-machines, after which he produced a patent clothes-pin. In 1860 he began the manufacture of a spring hook and eye, for which he also devised the machinery. Mr. Smith showed great ingenuity in inventing [he machinery by which his original articles were made. In addition to perfecting the ideas of other people that secured patents, he took out for himself nearly sixty, among which was that for the machinery that is now used in folding newspapers.

From Appletons Encyclopedia.

The Hartland Fair was well known for the agricultural exhibits. This is a photo of the fairground in 1940.

Hartland Fair 1940

This document was compiled by Howland Atwood in 1991. Except for some minor typographical and editorial corrections, what follows is exactly as he filed it in the Hartland Historical Library.

The Willard Cemetery is primarily a private family cemetery, located on the left, part way up Mace Hill. As in other cases, some neighbors were permitted to bury their dead there. Byron P. Ruggles made his survey of the Quaker Willard Grave-yard in August 1907 and he recorded nineteen gravestones. There are probably a few unmarked graves. The oldest gravestone appears to be that of Betsey, daughter of James N. and Abigail Willard, who died in 1800.

The Willard farm was the one owned and occupied by Willis Curtis. Whether or not the land once extended as far up Mace Hill as to include the cemetery lane is not presently known, although it would seem likely that it did. The farm now extends up to the Cobb Hill road, up to the Cobb place, which was probably sold off from the original farm. Just when the Billards came to that farm is not known either.

James Nutting Willard is not listed in Densmore’s Census of April 5, 1771 for Hertford (Hartland) in Cumberland County, Vermont, but his name does appear in the list of “Poles & Notable Estate of Inhabitants of Hertford” in 1778. (Hertford was changed to Hartland by vote of the legislature in 1782).

James Nutting Willard was of the fifth generation to live in America. His immigrant ancestor, Major Simon Willard emigrated from County Kent in England in 1634. Simon’s eleventh child, probably by his third wife, Mary Bunster, was Henry 2 Willard, who married, first, Mary Lakin of Groton. Their second child, Simon 3 Willard was born in Groton, Mass. Oct. 6, 1678. He married Mary Whitcomb and they lived in Lancaster, Mass., where he died in 1706. On Dec. 12th 1706, his widow married Samuel Farnsworth and she was the mother of Samuel, David, and Stephen Farnsworth, the first settlers of Fort No. 4 or Charlestown, New Hampshire. Moses 4 Willard, the second son of Simon 3, was born at Lancaster about 1702 or 3 and along with his half-brothers, the Farnworths, also became an early settler of Fort No. 4, removing there permanently by May 1742. Moses 4 Willard married at Groton, Mass. Sept 28, 1727, Susana Hastings. They had four children. Their second daughter, Susanna, married Capt. James Johnson. She became the mother of Elizabeth Captive Johnson, who was born in Cavendish near Reading, Vermont, while Mrs. Johnson was a captive of the Indians. The fourth child and only son was James Nutting 5 Willard of the fifth generation.

James Nutting 5 Willard married Abigail, daughter of Capt Ephraim and Joanna (Bellows) Wetherbee. The children of James Nutting and Abigail (Weatherbee) Willard, the first six probably born in Charlestown, N. H.:

Since the last three children are said to have been born in Hartland, James Nutting Willard must have brought his family to Hartland later in the year of 1772 or early in 1773. At least three of the James N. Willard children are buried in the Willard Cemetery, perhaps four or five.

Oliver Willard, one of the earliest settlers of Hartland was a first cousin of Moses 4 Willard, the father of James Nutting 5 Willard.

At some time in his earlier life James Nutting Willard became a Quaker and in his later years was usually referred to as Quaker Willard. The farm dog population gradually increased up to the point that Quaker Willard thought that he must destroy some of them, but he first told his children that each one could select his favorite dog to keep. So each child took a stand beside his favorite dog, saying, “Thee must not kill this one” and “thee must not kill this one” until there was only one left. Mr Willard called the remaining dog to him and said “Hast thou no friend among the children? Thou shouldst have a friend; I will therefore be thy friend”. So all the dogs continued to live.

***********

Note: the copy is not clear in many places, so some of this may be incorrect.

Lewis G., son of J. S. & C. Willard Died Oct 16, 1852 AE 19.

Nancy N., dau. of J. S. & C. Willard Died Oct. 12, 1852 AE 17.

Celendia W., dau. of John S. Jr. and Celindia Willard, died Sept 8, 1826 AE 7 years.

—

In Memory of James Willard Son of Mr. Ed. & Polly his wife. He died July 3, 1821 aged 2 years & 3 days.

—

Edw’d Willard Vt. Mil. Ref. War (A government marker) Since Edward was but 10 years old in 1775, he must have entered service towards the end of the war.

—

In Memory of Betsey Daughr. of James N. & Abigail Willard, died Sept. 29, 1800 AE 32 y. 11 m.

In Memory of Mrs. Abigail Willard, wife of Mr. James N. Willard, who died March 4th 1816, aged 76 years.

In Memory of James N. Willard, who died April 21, 1818 aged 83 years & 11 months.

Memento James Willard, died April 16, A. D. 1839 in the 76 year of his age.

—

In memory of Nancy, wife of John S. Willard, died Sept. 26, 1845 in the 75 year of her age.

John S. Willard Died Mar. 16, 1852 AE. 80.

—

In Memory of John S., Son of John S. and Nancy Willard, aged 1 year, 9 months, and 26 days.

—

Thales Willard, died Sept 10, 1829 in his 56 year.

Thales Willard died 1839, aged 75. (Ruggles record [1907], this gravestone not found in 1991).

—

Edwin Smith, Died Sept. 27, 1828 AE. 23 years.

Susan Lane, daughter of Capt. Samuel & Amelia Whitney, died Aug. 8, 1833.

—

Eliza C., Wife of Martin L. Peterson, died July 1, 1828 AE 29 years.

(This gravestone is half imbedded in a large pine tree on its left.)

The Christian names were supplied by the B. P. Ruggles record.

—

Azubah, wife of Aaron Hunt Died Oct. 1, 1828 AE 52 years.

—

HARTLAND IN THE CIVIL WAR

Fifth Installment, January, 2014

by Les Motschman

The War Becomes a Crusade

The fourth Hartland Historical Society Civil War newsletter of last June ended with the Battle of Gettysburg July 1, 2, and 3, 1863. In this issue, I will wrap up descriptions of the “nine months” men’s service, and recognize Hartland men who joined the army in the second half of 1863. As after Gettysburg there were no major battles in 1863 where Hartland men would have served, I will take the opportunity to describe how after two years of hard fighting, the war changed in some aspects. Lastly, I received interesting responses from four HHS members regarding their family members’ involvement in the war.

The 40 or so Hartland men who enlisted for nine months in the fall of 1862 after President Lincoln called for 300,000 volunteers were mustered out of the Army in the summer of 1863. Most of the Hartland men joined the 12th Vermont Infantry Regiment, the first of the five Vermont regiments to make up the 5,000-man Vermont 2nd Brigade. The 12th was the first to form up at Brattleboro, the first to leave for Virginia, and thus the first to come home. Its members were mustered out of the army at Brattleboro on July 14, 1863. Seven Hartland men joined the 16th Regiment, which was the last of the five to form. They were mustered out August 10, 1863.

In a talk I attended, Howard Coffin said that the 2nd Vermont Brigade, whose term of enlistment was nearly over, was detailed to bury the dead at Gettysburg. Soon after Gettysburg, the enactment of a new draft led to demonstrations and riots in many locations throughout the North, including Irish quarry workers in West Rutland. The New York City riots were the worst, where there was extensive property damage and 250 killed or seriously wounded. Some of the returning Vermonters volunteered to go to New York, but they were not sent. Instead, seasoned combat troops from the Army of the Potomac, including Vermont’s 1st Infantry Brigade, and presumably some Hartland men were sent north to quell the rioting. Unlike the police, they did not hesitate to fire into the rioting mobs. Some soldiers who survived Gettysburg and the fierce fighting in Funkstown with Lee’s retreating army were killed in New York City.

It’s not surprising that many of the men who enlisted early in the war, mostly motivated by patriotism, looked down on the “nine months” men, who enlisted for such a short term and for such big money. The three-year men in Vermont’s 1st Infantry Brigade, who went from one great battle to another, referred to the men of the 2nd Brigade who spent most of their short service in camp as “Nine Monthings hatched from two hundred dollar bounty eggs.” Colonel Farnham, a 2nd Brigade Commander, thought the “nine months” strategy to fill the ranks a terrible waste and bad for overall morale. Just as the Brigade was ready for fighting, it was disbanded and sent home.

Certainly the heroics of the 13th, 14th and 16th regiments at Gettysburg earned the “nine months” men a measure of respect. All the men who volunteered did what was asked of them, and those thrown into the thick of battle performed bravely. None of the “nine months” men from Hartland died in combat, but several young men died of disease. From my perspective 150 years later, I’m inclined to believe that many of the Hartland men of the 12th and 16th were quite proud of their service. The war was probably the most memorable event of their lives. I have a list of 50 Civil War veterans buried in Hartland (many left town after the war), and I have visited about half of their graves. The young men who died early in camp were usually sent home and buried in the family plot.

What is telling is how many gravestones of men who died when elderly feature their unit right under their names. Sometimes that is all that is on the stone, other than birth and death dates. Many of these men died decades after their service, yet this small piece of their life from when they were young is prominent on their gravestones.

-1-

Gravestones of two brothers who died a month apart, Plains Example from Village Cemetery: Cemetery (Austin was in the 4th Vermont Regiment): John F. Colston J. P. Hutchinison Austin Hutchinson Musician Co. B 12th Reg. VT. Vols. 7th VT Inf. Died at Camp Griffin, VA 1841–1921 d. Mar 20, 1862 d. Feb 4, 1862

The Emancipation Proclamation

January 1, 1863

The overall title of this installment (The War Becomes a Crusade) comes from Howland Atwood’s 1963 Hartland in the Civil War, where he dedicates only a few paragraphs to Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Lonnie Bunch, Director of the Smithsonian National Museum of African-American History, said on NPR’s Tell Me More program in early January 2013 that the Emancipation Proclamation is one of the most misunderstood documents in American history. Most people think it freed the slaves, when in fact slavery ended when the 13th Amendment was ratified on December 6, 1865. The Emancipation Proclamation began the process of emancipation when the Federal government said that slavery is wrong and it must end. Bunch said Lincoln realized that he could impact the South by taking away its workers, encouraging them to come North to work or maybe even join the Union Army. It would also add a moral tinge to the war. It’s clear that Lincoln felt that if he could end the war and restore the Union without ending slavery, that would be all right with him. The war had been going on for two years, and it wasn’t going well for the Union. Lincoln knew he had to do something bold, but he waited until the Union victory at Antietam so he could speak with more authority. For Lincoln it was an evolving situation. As soon as the war broke out, hundreds and then thousands of African-Americans fled to the Union lines. This put pressure on the North to say what it was going to do with all these people.

When he was asked, “How was the Emancipation Proclamation received?” Bunch replied, “In a variety of ways.” European nations such as England and France saw that it put a stamp of moral authority on the war. While such countries depended on the cotton that slaves produced, they decided not to recognize the Confederacy. Of course,

the abolitionists and the free black community really supported it and felt it was the beginning of the end of slavery.

Even so, many in the North asked, “Why is Lincoln making the war about slavery?” That notion didn’t go over well in the Northern Army, and many soldiers let it be known they didn’t join up to free the slaves.

Howard Coffin, in Nine Months to Gettysburg, writes that despite Vermont’s history of abolitionism, despite its 1777 Constitution as the first to outlaw slavery, and despite its role in the Underground Railroad, many of the men who fought held racial attitudes not much different from those of their Southern counterparts. What is clear, though, is that a profound reverence for the Union is what spurred many men to join the Army.

A Boston Globe article at the time of the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation noted that before the war slaves comprised the largest single financial asset in the United States. Some considered the freeing of the slaves the greatest confiscation ever of private property by the Federal government.

The November 30, 2012, Vermont Humanities Council weekly “Civil War News” noted that President Lincoln for years had favored the colonization of free blacks outside the United States. By the time of the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln was referring to slaves as Americans of African descent and asserting that objections to colored people remaining in the country were malicious.

-2-

The 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment

President Lincoln made emancipation a tactic and a goal of the war, and with it opened the military to black soldiers. Massachusetts soon became the first to call for the raising of black regiments. Frederick Douglass, a leading black activist of the time, threw himself into the effort, urging African American men throughout the country to come to Boston to join up. Hundreds did, free and fugitive alike. Of course the units would have to be segregated because even in the North most white soldiers would not serve alongside blacks. Then, the problem became who would lead them. Governor John Andrew, an abolitionist, asked 25-year-old Robert Gould Shaw, the son of a wealthy abolitionist who lived on Beacon Hill, if he would take command of the 54th. Shaw, who had been in the Army since the start of the war, reluctantly accepted, and started training the regiment. In April 1863, he was promoted to Colonel and married his sweetheart. On May 28, 1863, the Regiment marched through Boston to the cheers of a massive crowd to board ships to Hilton Head, South Carolina.

The 54th fought well in limited action, so when an attack on Fort Wagner was planned, it was given the honor of leading the assault. Moving across open beach, the 54th came under heavy fire. Colonel Shaw sprang to the front and led his men as they charged. As he waved them on, he was shot through the heart. Despite the valor the 54th displayed, its assault was repulsed, and nearly half of the men were killed or wounded. Disregarding custom, the Confederates stripped Shaw’s body and threw it into a mass grave with his men. When commanders later offered to make an effort to recover the body, Shaw’s father replied that that would not be necessary, as his son would have preferred to rest with his men.

The 54th is famous. In 1883 a Boston committee commissioned sculptor Augustus St. Gaudens to create a memorial for Boston Common. It was to be complete in six months, but it took him fourteen years, and it’s a magnificent work. The 1989 film, “Glory,” tells the story of Colonel Shaw and the men of the 54th. Most of the information for my piece comes from the Boston African-American National Historic Site on Beacon Street, near the memorial and across the street from the Hooker entrance to the Massachusetts State House.

Note: The Shaw/54th Memorial is across from the State House on the highest corner of Boston Common. Having attended college on Beacon Hill and visited the city at least a dozen times a year in the ensuing 47 years, I have stopped to look at the Shaw Memorial dozens of times. I did not know the story behind it until the film, “Glory”, and then I thought the memorial showed the unit marching into battle. A year after starting this project, I went to the small museum in the Fairmont Hotel on Battery Wharf where a recruiting poster for “Colored Men of African Descent” caught my eye. The text under the poster described the memorial as depicting the 54th passing in review in front of the State House, headed for Battery Wharf to board ships for South Carolina. I thought after all those years that I finally really understood what the Shaw Memorial is all about. On a subsequent trip to Boston, I visited the memorial with the knowledge that it showed the 54th passing in front of that very spot. Then I realized the men are shown marching west on Beacon Street instead of east down to the waterfront.

I talked at length with Gregory Schwarz of the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site. He has written a book about the Shaw/54th Memorial. He said the original plan was for the memorial to be across the street on the State House grounds. This would explain why it appears backwards to me, except that Gregory Schwarz said Saint-Gaudens was aware of the change when he started the project. A picture taken at the 1897 dedication ceremony shows veterans of the 54th in formation marching east in front of the memorial in the opposite direction of what is depicted in the sculpture. In any case, you can see a bronze casting of the Memorial that was done in 1997 for the site in nearby Cornish, New Hampshire.

I hope Hartland Historical Society readers enjoyed reading about the 54th Massachusetts and the Shaw Memorial. I am sure some of you wondered what that has to do with Hartland in the Civil War. Readers will probably be as surprised as I was to learn that Hartland is credited with sending three men to the 54th. Austin Hazard, Sylvester Mero and Henry Parks were mustered in on January 22, 1864, so they would not have been involved in the events described above. They served until August 1865, a few months after the war ended. Hazard was a butcher and

-3-

thirty-two years old when he enlisted. Nineteen-year-old Mero was listed as a farmer and as having been born in Woodstock. Less is known about Parks and he is not on the Vermont in the Civil War roster for Hartland, but his name is in the March 1864 Hartland Town Report. These three ‘volunteers’ were among thirty-six who received $500 bounties that year. It is not always easy to determine from the roster who was from Hartland as men often enlisted in neighboring towns or even traveled to towns desperate to fill their quota and offering higher bounties. [The recruiting posters for the 54th in Boston were offering $100 bounties.] The three enlistees in the 54th may have been part of a black community that existed in Woodstock. The Vermont in the Civil War website indicates that there were over seven hundred African Americans living in Vermont in 1860. One hundred and forty-nine served in the Union Army.

Men credited to Hartland who enlisted in late 1863 or early 1864 by unit

| 3rd Vt. Inf. Reg.

Dana Boyd Almeron Burnham* David Churchill Richard Smith 5th Vt. Inf. Reg. Moses Lafayette Joseph Mayo*** 1st Vt. Light Artillery Battery Daniel Clough John Cutler U. S. Sharpshooters |

6th Vt. Inf. Reg.

Henry Carlisle Charles Cleveland Harry Durphey William Durphey David Elkins Josiah Elkins William Elkins James Emery Ira Hadlock Stephen Huntley Joseph Jones** Benjamin Rickand Horace Sargent Roger Sargent George Sartwell Heaton Skinner Henry Tilden |

7th Vt. Inf. Reg.

John Cook Francis Hale 9th Vt. Inf. Reg. David Barber George Mitchell Ransom White 11th VT. Inf. Reg. Benjamin Hill Elisha Spaulding 54th Mass. Inf. Reg. Austin Hazard Sylvester Mero Henry Parks |

| * Died of disease 2/17/1864 ** Died 2/18/1864 *** Joseph Mayo was the only one of the nine-months men to re-enlist at this time. |

||

After serving two years in the 6th Vt. Regiment, Perry Lamphere re-enlisted 12/15/1863 and died of disease 1/1/1864.

The Gettysburg Address

November 19, 1863

The short speech President Lincoln gave at the dedication of the National Cemetery at Gettysburg is well known and regarded as one of the most important moments in American history. There is no need to report on it here, except as it relates to the theme of this installment. In the speech, Lincoln articulated why, because of the war’s terrible cost and suffering, it was then important to strive to create a better and freer nation than had existed before the war.

-4-

From Hartland Historical Society Newsletter Readers

We received a nice letter and copies of family “treasures” from Marion Rodgers Howard of Florida. She makes a claim that I doubt few could match. Marion remembers meeting her Civil War veteran grandfather! In her words, “I wonder how many living adults can call a Civil War veteran ‘Grandpa’? My Grandpa, William Wallace Rodgers, died in 1926. I was born to his oldest son Walter Rodgers in 1923. I remember Grandpa at our family Thanksgiving in Temple, N.H., in 1926 slightly before his death.”

Marion sent along a 1911 picture of 14 members of the Rodgers family, including her father and grandfather. She also sent two good pictures of Civil War camps. Unfortunately, they are not identified. A very old picture of her great-uncle Charlie was of special interest to me. I described in the second installment of Hartland in the Civil War that his tombstone in the Weed Cemetery caught my attention soon after we moved to Weed Road nearly 40 years ago. The stone indicated that Charles Rodgers was with the 12th Regiment Vermont Volunteers and that he died at the age of 18. I didn’t know he died of disease in a Virginia camp after only one month in the Army until I started this project. I never dreamed that I would someday know what the young man looked like.

The Rodgers brothers lived near the “Cream Pot,” as did their cousins Augustine and Daniel, and all were in Co. B of the 12th Infantry Regiment. Howland Atwood writes that William returned to the farm after the war and lived there many years. William is buried in the Village Cemetery. Augustine, the same age as Charlie, died in the 1890s and is buried in the Weed Cemetery. Daniel at 22 was the oldest of the four when they enlisted. He lived the longest. My records indicate that before he died in 1931 at the age of 91, and he probably was the last living Civil War veteran from Hartland. Daniel is buried in Morrisville.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Carol McArthur Rumrill supplied information about her and Deana McArthur Dana’s great-grandfather, Johnson Ames McArthur. He was living in Vershire when he enlisted in the 15th Vermont Infantry at age 22. His service as a “nine months” man was from October 22, 1862, to August 5, 1863. Howard Coffin in Nine Months to Gettysburg writes that the role of the 15th in the Gettysburg Campaign was similar to that of the 12th, which included most of the Hartland “nine months” men.

In late June 1863, General George Stannard was leading the five regiments of the 2nd Vermont Brigade from the Virginia camps north to Pennsylvania. After a week-long march, they reached Pennsylvania where a commander ordered General Stannard to post two of his regiments to guard the Corps’ wagon trains. The 12th and 15th stayed with the wagons while the 13th, 14th, and 16th continued on to the battlefield. Later in the day, Major General Daniel Sickles, commanding the Third Corps, which was also heading north, came upon the Vermonters and thought there were too many fine-looking soldiers guarding the wagon train. He brashly ordered the 15th to join his command and proceed to Gettysburg. Reportedly, the men gave a rousing cheer when they learned they would be joining the battle. The 15th joined the other Second Brigade regiments very early on the second day of battle. Just in time for break- fast, supply wagons had moved to the front line under the cover of darkness to feed the men they knew to be short of rations. Two companies were ordered to guard the ammunition wagons at Rock Creek Church, 2-½ miles away. The rest of the 15th marched over 20 miles back to Westminster, Maryland, to join the 12th Regiment guarding the Corps’ wagon trains, made up of hundreds of wagons and hundreds of cattle.

-5-

After the war, Johnson McArthur settled in Hartland, moving to the brick house on the Quechee Road where George and Carol Little have lived for many years. Mr. McArthur died in 1902 and is buried in the Village Cemetery. McArthur Brook runs through the former McArthur farm under the Quechee Road, Route 5, I-91, and the railroad to fall over Bish Bash Falls and into the Connecticut River.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Hartland Historical Society Board Member Diane Bibby gave me a newspaper death notice describing her great-great uncle’s life. It is titled “Big Pete Aubrey’s Death.”

Mr. Aubrey was born in Rouse’s Point, New York, of French descent, his grandfather having come to this country before the Revolution. His ancestors were all fighters in various wars. He learned the blacksmith’s trade, which he pursued in Rouse’s Point and later Malone. He married in 1851 when he was 18 years old. When the Civil War broke out, he enlisted in Co. G of the 98th New York. Aubrey went through the Peninsula Campaign, taking part in the battles at Williamsburg and Yorktown, where he was slightly wounded in the head by buckshot. Then came Fair Oaks, Chickahominy, Seven Pines, Malvern Hill, and the Seven Days fight. When his term of enlistment was up, he returned home to his trade. In 1863 he moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, where he obtained government work. In October he again enlisted, joining Co. G of the 2nd Regiment Heavy Artillery. The company was first stationed in Norfolk, Virginia, and then sent to Fort William on the Roanoke River in North Carolina. The fort was attacked by 30,000 rebels on April 17, 1864. For three days the rebels were held at bay, but on the 20th the Union troops were obliged to surrender. They were put aboard a freight train, packed into the cars like cattle, and taken to Andersonville prison camp in Georgia.

Mr. Aubrey was a strong, robust, hardy man when he went to war, but he was so weakened by the privation he suffered in prison that he was not able to work or accomplish much after the war. He got by on a pension of only $16 a month, despite what he had offered his country. He was too little appreciated or honored in life, given that service. He was a member of the Grand Army Post and Anderson Survivors Association. Leaving a wife and nine children, he died on January 6, 1897.